A Rowan farm’s holly still links past Christmases to the present

Published 12:00 am Sunday, December 24, 2017

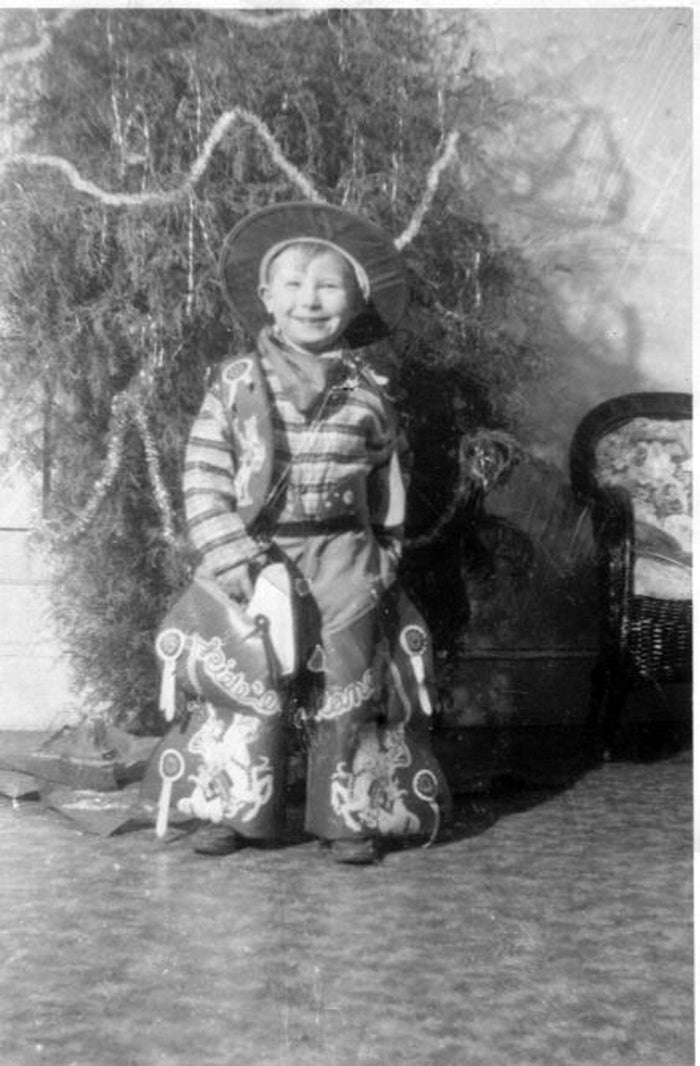

- Photo courtesy of Donald Kesler Dressed as a cowboy, a young Donald Kesler stands in front of the Christmas tree. Now in his 70s, Kesler says he was about this size and age during the Christmas when his family was hit with bad news.

By Donald Kesler

For the Salisbury Post

The lights and ornaments are coming down from the attic. The candles readied for the window. The tree will soon be inside. And the memories abound.

As long as I can remember, we always had a tree when I was a child — not one bought at the corner lot, but a real tree from the woods, usually a cedar but sometimes a pine. No matter what kind, it was always way too tall for the room, not that Dad didn’t always tell us that it would be.

But we would never listen, so it was always too big.

As part of the adventure of finding a tree, we always went to a certain place in the woods to cut some holly. The old holly tree was big even when I first saw it and it was several years before I heard the story of how my grandmother would send Dad into the woods to get holly when he was 6 or 7.

The tree was old when he would go and he had heard the same stories about when his dad would be sent to collect the holly for Grandma Babe, my great-grandmother.

The location of the holly tree was somewhat a mystery to me as a kid. When roaming the woods during the summer, I would sometimes find it, but my trail was so diverse, I could not have given good directions.

Those woods held many secrets, varying from an abundance of Indian arrowheads to dozens of pits from the glory days of the Carolina gold rush. There was even a real gold mine surrounded by a fence.

I had never seen the bottom of that mine but had tried many times.

Things were different that Christmas I turned 6 years old. An early morning phone call had aroused my parents. I stayed in bed to keep warm until the stove in the kitchen could be stoked up and a fire roaring.

When I did get up, there were no eggs and bacon — only corn flakes — and I could see that my Dad had tears in his eyes. He quickly left the house without saying anything to me, but I knew something was really wrong.

I seldom saw Dad between his job as a fireman and his second and third jobs in various other attempts to pull us out of poverty. Of course, I didn’t know we were in poverty — the secondhand clothes and drafty four-room house were just what I was used to.

And besides, only that past summer we had a real bathroom added to a porch Dad had enclosed. It had even been a little nice to see the small pile of snow in the corner of my room last winter.

But something was very wrong, and soon my mother sat down beside me and tried to break the news. My dad’s mother — my grandmother, my tie to the farm, a big piece of my life — had died.

How could that be? She had come through the operation very well and was to be heading home. We were even planning to go visit her at the farm in a few days. We were going to take her some food so she wouldn’t have to cook for Grandpa.

How could this be?

The next thing I remember was being in the farmhouse dressed in my hand-me-down suit and my hand-me-down shoes. My dad’s tie was so wide that it was more like a bib than a tie. And the house was full of people. Some I knew as family, some I knew by sight, but many I had never seen before.

There were my uncles — Troy and Norman — and aunts Aileen, Hazel and Ann.

There were great-uncles and great-aunts and people from the church. Everyone had to pat me on the head and ask me how old I was, and did I want something to eat and didn’t my grandmother look nice laying there and …

I could not take it any more, so I slipped off into another room and found my favorite chair that had be moved from the living room to make room for the casket. It was the velvet over-stuffed chair that I knew so well, that piece of safety where Grandma had read me stories, that place I knew.

I woke up smelling food, even a banana cake, and I wanted to jump up and ask Grandma for a piece. But when I got to the kitchen, she was not there and I remembered where she was … in the living room in that box.

I could not eat, I couldn’t even talk, so I ran outside toward the barn and the horses I loved and the smells I wanted to keep forever.

Christmas was not a joy that year. The tree came from the little woods behind our house in town, and there was no trip to find holly. It was as if the season had no savor, like the salt I had heard about in church.

The woods, the trees, the gold mines and the holly tree were like they were in another world.

It was three years later, when I was no longer an only child, that Dad took John, my 3-year-old brother, and me to the farm to get a Christmas tree.

After finding the right tree, Dad pointed in another direction and we soon were looking up at that giant holly tree that I had remembered.

Dad smiled and told us both how his mother had always sent him out to collect holly for Christmas and how his father had done the same as a boy. As he spoke, the world became fresh again. The season regained its savor and I became whole again.

We could now talk about Grandma and think of the future.

We repeated this search each year through my teens, bringing with us another brother, Charles.

We boys have often done the same with our children and now grandchildren. We have gone so far as to purchase the tract of land where the tree still lives and grows even bigger and with more meaning … our ancestral holly.

Salisbury native Donald Kesler is a retired nuclear engineer and author living in Matthews who has fond memories of his family’s farm in eastern Rowan County.