Women working to change our perspective

Published 12:00 am Sunday, March 25, 2018

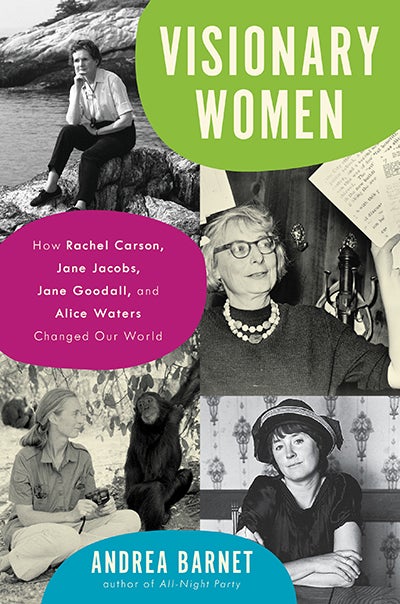

- Visionary Women: How Rachel Carson, Jane Jacobs, Jane Goodall, and Alice Waters Changed Our World

“Visionary Women: How Rachel Carson, Jane Jacobs, Jane Goodall, and Alice Waters Changed Our World,” by Andrea Barnet. Ecco. 514 pp. $29.99

By Joanna Scutts

Special To The Washington Post

They were single and married, mothers and not, educated and self-taught, financially comfortable and struggling. Their work spans the second half of the 20th century and continues into the present. They did not know one another.

But in her lively new biography of Rachel Carson, Jane Jacobs, Jane Goodall and Alice Waters, Andrea Barnet makes a compelling case that these women “changed our world.” Environmentalists in the broadest sense, their vision — and actions — on conservation, she shows, are nothing short of revolutionary.

“Visionary Women” links her subjects chronologically, with an emphasis on the 1960s. It was then that the women became, collectively, “a kind of true north for the gathering counterculture.” They were Davids aiming slingshots at the Goliath of postwar America, which was waging an all-out “war on nature” with wrecking balls and toxic pesticides, paving paradise to put up a vast suburban parking lot.

Price of progress

In “Silent Spring” (1962), Carson shocked the nation by laying bare the enormous environmental cost of technological progress.

Jacobs, in turn, was fighting to keep another fragile and beautiful ecosystem — her New York City neighborhood — from being flattened by the highways whisking white families to the suburbs.

Meanwhile, Goodall camped for months in the jungles of Tanzania to bring back reports of the intelligence and sociability of chimpanzees, which upended the scientific establishment’s assumption of human supremacy.

Finally, Waters, more product than driver of the counterculture, built a restaurant and a worldwide reputation on the idea that the best meals were created in a respectful symbiosis between environment, farmer, chef and diner.

The ’60s saw the gathering of the second feminist wave, and Barnet writes that Betty Friedan might be considered a fifth “visionary” in her lineup but for the violence of her approach, her desire to blow up the system rather than safeguard what is valuable.

Yet Barnet is careful not to rely on essentialist assumptions about gender. When she describes Carson’s style of fostering connection rather than competing with her peers as “female,” the word is set off in scare quotes. Her subjects’ femaleness mattered most, unsurprisingly, to men: It was what they saw first and what some of them could not see past.

Over and over Goodall fended off the sexual advances of her much older mentor. Carson was dismissed by her critics as a cat-loving spinster, and Jacobs as a “sentimental Hausfrau.”

Jacobs embraced her maternal identity, deploying local children, her “little elves,” to knock on doors, gather signatures and draw the attention of the press. It was a way of forcing into the foreground the future that her opponents refused to acknowledge.

Dreams and exclusion

Beyond their iconoclasm and remarkably supportive families — and of course, their gender — the main biographical trait these women share is that they all are white.

When Barnet writes of the complacent world into which Carson’s “Silent Spring” would erupt, “People looked inward to home and family, diverted themselves with easy pleasures, [and] turned a blind eye to social and racial injustices,” she means white people — those who, like her subjects, were the intended beneficiaries of the vast postwar technological and consumer boom.

Barnet, whose previous book was about the women of Greenwich Village and Harlem in the 1910s and ’20s, acknowledges that the cliché of the suburban American Dream was based on segregation and exclusion. She observes that Jacobs testified to a Senate subcommittee in 1962 about endemic racism at the Federal Housing Authority and that her ideas about the failures of housing projects influenced James Baldwin, yet we don’t hear voices from communities of color — the main targets of urban-renewal policies.

Elsewhere, Barnet might have noted, in her discussion of the rise of agribusiness, that the patterns of racial exclusion that created the suburbs also affected rural areas, with black farmers routinely denied federal assistance to save their businesses. That less than 2 percent of the country’s farmers today are African American should affect how we understand the “farm to table” relationship and who benefits from efforts to improve the food supply.

Likewise, if there has truly been a “paradigm shift” in the way Americans value the natural world since Carson’s book was published, it needs to extend to an understanding of the central role of race in environmental catastrophes like the Flint, Mich., water crisis.

Still, Barnet makes a powerful case for a shared perspective among her subjects, likening Carson’s understanding of the sea to Jacobs’s view of the city, as “a balance of live and ever-evolving forces, a fluid network of exchanges, as much a process as a place.” Goodall recorded everything about her chimpanzees in capacious detail, without hierarchy or categorization, looking “with a kind of blinkered intensity, drawing upon all her senses.”

Waters, a young student in France, recalled lavishing a similar attention on “what the fruit bowl looked like, how the cheese was presented, how it was put on the shelves, how the baguettes twisted. The shapes, the colors, the styles.”

All four women learned by immersing themselves in their environment and letting their eyes lead the way. Of the many lessons they have to teach us, this may be the most potent of all: Pay attention.

Scutts, a literary critic and cultural historian, is the author of “The Extra Woman: How Marjorie Hillis Led a Generation of Women to Live Alone and Like It.”