‘Dreamland:’ Anatomy of opioid addiction

Published 12:00 am Sunday, May 6, 2018

- Rowan County's Second Annual Opioid Forum will include an appearance by the author of 'Dreamland: The True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic.'

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

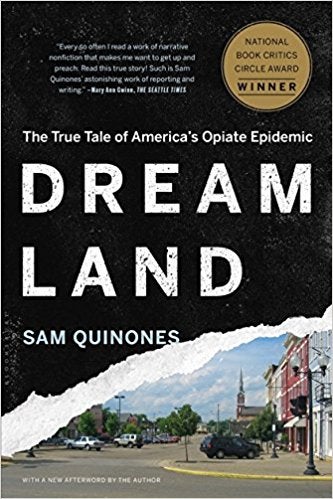

Sam Quinones’ book, “Dreamland” is exhausting — fascinating, important and mind numbing after a while.

Quinones won the National Book Critics Circle Award for his 2015 work, for which he did years of research. He set out with a daunting task — to uncover, collate and describe how America got its insatiable appetite for opiates and the even more potent drug, heroin, specifically black tar heroin.

Quinones will be in Salisbury May 15 as the keynote speaker for the second opioid summit, 3-9 p.m. at West End Plaza.

Two things to take away: Pharmaceutical companies started the epidemic of opioid abuse by promising doctors that OxyContin is not addictive; that assurance was based on a misinterpreted letter to a medical journal. It was later cited as extensively researched, which it was not.

Second, people barely surviving in dusty spots on dirt roads discovered the magic of retail sales, which provided them the money, land ownership and prestige a job in a factory could never match.

Quinones discovered that a tiny place on the Pacific coast of Mexico, Xalisco, in the small state of Nayarit, was the origin of some of the most successful heroin distributors in the U.S. Supply, meet demand. Demand, your supply is just a phone call away.

The opioid prescriptions came before the balloons of black tar — a purer form of heroin — but not by much.

Where America was an eager market for marijuana and cocaine, those drugs were often sold by gang members in bad parts of town. Getting your fix could be dangerous. Gang wars erupted over territory.

With heroin, it was a bunch of young men, taking orders from a cell leader and providing friendly, clean delivery from a respectable car window. If you had a problem with delivery or service, the cell managers fixed it with free drugs or a deal on multiples. Once the young man had been driving for a while, he went home with his cash, his Levi 501s, and impressed his family.

“Dreamland” is dense, full of accounts of the young Mexican men trying to live a better life. Quinones tells about numerous addicts turned informers, who explained the distribution to him.

Then he dives deeper in the painkiller epidemic, pointing fingers not just at the makers of the drug, but at its sales force, at the doctors who fell for the pitch and at the shady medical personnel willing to make a fast buck by setting up a prescription mill to supply “patients” in pain.

Quinones, who has lived in Mexico, became obsessed with the stories of addicts and suppliers and he kept digging to find more, providing one explanation after another about the perfect storm that arose to rain down terror on a country eager to be pain free — in all things.

In an afterword written for the 2016 paperback edition of the book, he writes:

“Heroin is, I believe, the final expression of values we have fostered for thirty-five years. It turns every addict into narcissistic, self-absorbed solitary hyper consumers. A life that finds opiates turns away from family and community and devotes itself entirely to self-gratification by buying and consuming one product — the drug that makes being alone not just all right, but preferable.”

Quinones blames society — American and white, in particular — for believing that being pain-free is a birthright — not just physical pain, but emotional.

This is a book that will have you exclaiming aloud, sharing paragraphs with friends and spurred, Quinones hopes, to do something.

He writes that at the beginning of the opioid epidemic, rich white parents were in denial about what their teen-agers were doing, and that even when one died, it was kept quiet.

The role of big medicine in the addiction story is truly shocking. Studies argued that patients had a right to be pain free. It became part of their vital signs, and the 1-10 pain scale became a common question.

Once the magic molecule in opium derivatives was isolated, it became the panacea for a world of painkillers. Early studies suggested that a time-released dose of OxyContin would not lead to addiction, because the patient was in so much pain. Where once those drugs were reserved for dying cancer patients, the false evidence that it was not addictive and heavy lobbying by one pharmaceutical company in particular, Purdue, convinced doctors that OxyContin was an acceptable pain killer for knee pain, wisdom tooth extraction and the like. Anyone could ask for something for pain and easily get OxyContin. It became like aspirin for many.

When Purdue sent out a worldwide sales force of more than 100,000 people urging doctors to use the magic pill, they pleaded on patients’ behalf. They deserved to live without pain.

Down the road, when some doctors saw addiction and balked at prescribing OxyContin, patients turned to clinics where all the doctor did was write a prescription. One clinic, Quinones reports, wrote 300 prescriptions a day, spending less than 90 seconds with each patient.

Where addiction was once the problem of inner cities, the new opioid addiction was showing up in the country club set, from Dad’s golf injury to junior’s twisted knee.

Cities like Los Angeles were known for the ease of finding any kind of illicit drug; painkillers were portrayed like knights in shining armor. The boys from Xalisco quickly learned to expand their markets east from California, into towns like Portsmouth, Ohio, the hollows of the Appalachians, Charlotte, and, as we’ve seen in this newspaper, Salisbury.

“Dreamland” is an important book. It — or excerpts from it — should be required reading for all parents and caregivers, not to mention those in the medical profession and especially, law enforcement.

Quinones ends up optimistic that the community can stem this tide. He is, perhaps, a little premature.