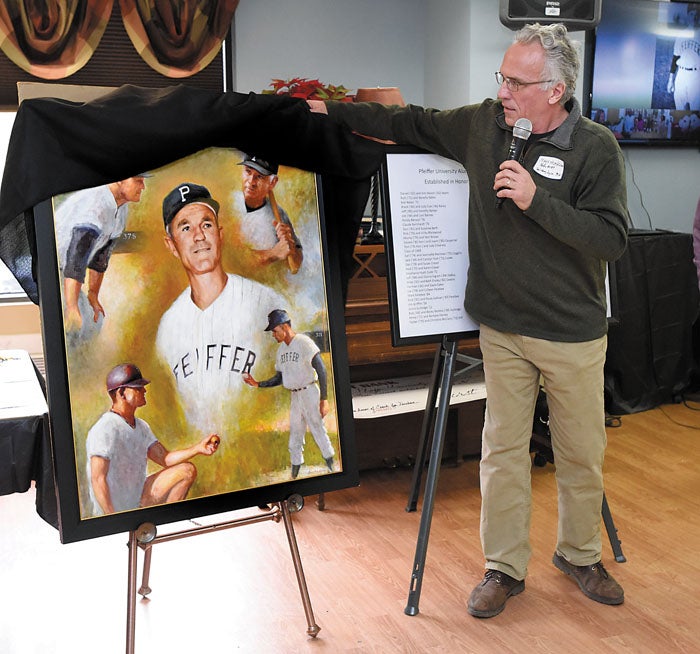

Joe Ferebee, legendary baseball coach, nears 100 years old

Published 12:45 am Sunday, February 17, 2019

By David Shaw

sports@salisburypost.com

ALBEMARLE — The guest of honor barely uttered a word, but no one complained. Joe Ferebee could always say more with his eyes, anyway.

On the occasion of his 100th birthday — which actually falls on Feb. 24 — the baseball coaching legend with far-reaching influence and more than 1,400 career wins printed on the back of his bubble-gum card, managed only a brief smile. And that, quite simply, said it all.

“This man,” said Bob Gulledge, organizer for Saturday’s well-attended extravaganza at Stanly Manor, “has touched so many lives. Look at all these people — and this is just a fraction of it. We’ve been doing this for 10 years now, ever since he turned 90. I made him promise he’d be here for 100, and here he is. He wanted this day.”

As he begins his 11th decade, Ferebee is confined to a wheelchair and speaks softly, if at all. His children say he has good days and bad days. Six months ago, he worked his way out of a double-pneumonia jam and emerged with yet another time-honored story to share.

“Yesterday, he was full of life,” oldest son Joe reported. “Today, not so much. But he could always remember these minute details. Like, he’ll be talking about some game from 1954, and he could tell you what the score was in the bottom of the seventh inning and if a blue jay flew over the field.”

Right there, you have a snapshot of how perceptive Ferebee still is. He seemingly has seen it all, yet hasn’t seen enough. “He remembers a lot more than sports,” said Mark Ferebee, another son. “He tells us he was a double-major at Catawba and never missed a day of classes.”

There’s no doubting that. Of course, Ferebee’s long-ago interests extend beyond the foul lines. He spent years enjoying hunting, fishing, wildlife, bird-watching and even poetry. But on the field and in the dugout, where most of his glory moments are documented in black & white, his coaching technique and penchant for winning remains unmatched. He triumphed 694 times as Salisbury’s American Legion coach, 677 times for Pfeiffer College and led Boyden High School to a state title.

“I know why,” said 81-year old Salisbury native Tommy Eaton, a cagey left-handed pitcher for the 1955 prep and Legion state championship teams. “Because he was always a teacher. We worked on important things that nobody else worked on — cutoff plays, backing up throws, throwing to the right base. Little things like that could turn a game around. He even taught us how to properly wear our uniforms, our hats and our socks. He’d say, ‘We may not be able to play ball, but we’re going to look like we can.'”

Ferebee’s teams looked the part for more than four decades. Consider that 42 of his former players signed professional contracts and a fortunate handful reached the major leagues — including pitcher Monty Montgomery, a ’69 Pfeiffer grad who spent parts of the 1971 and 1972 seasons with the Kansas City Royals.

“It’s all because of Coach Ferebee,” he declared. “I started in ’64, when Pfeiffer first became a four-year school. From the first day of practice until the last, he hit hard on fundamentals. I think he was recently compared to (Tommy) Lasorda. That man sitting over there is the best baseball coach I’ve ever been around.”

Memories like that made fine souvenirs for impressionable young men, but some of Ferebee’s lessons have yielded lifetime harvests. Listen to Leon “Bear Creek” Smith, a Pfeiffer basketball player from 1958-60 and a student in one of Ferebee’s P.E. classes:

“I give him two thumbs up as a teacher,” he said. “If I had three hands, it would be three thumbs up. I remember when he had an outdoor class, he’d invite me along because I could mimic some of the animals and birds he was teaching about. He made you feel like you wanted to please him, which was a gift.”

Randy Benson, a Cardinals’ scout for 12 years and star of the 1969 American Legion state championship team, remembers Ferebee’s reaction to his two-out, two-run walk-off homer at Newman Park.

“He jumped about about three or four feet in the air,” Benson recalled. “The ball cleared the wall by about three inches and it came against (Wilmington’s) Dave Sandlin, who had no-hit us earlier in the tournament. The best line came from Marty Brennaman, the radio guy. He said, ‘That pitch had suntan oil all over it,’ because it sent us to (the regionals) in Florida.”

Ferebee played a decisive role in Griggy Porter’s life path. “Because of his connections, I got a chance to play,” he said. “He was strict with me. What he said, you better do.”

An infielder and ’69 Pfeiffer grad, Porter batted .320 for the Cubs’ Wichita triple-A farm team in 1972. But as a U.S. Army reservist, he spent two weeks that summer fulfilling his military obligation. “I left on a Friday,” he recalled. “And (Chicago second-baseman) Glenn Beckert broke his ankle on Saturday. That’s how close I came.”

Hard-throwing southpaw Joe Barnes — a 1966 Pfeiffer graduate who traveled 1,800 miles with his wife to attend yesterday’s celebration — still regrets not asking Ferebee for advice after the Reds selected him in the 15th round of the ’65 MLB draft.

“It’s the biggest mistake I ever made,” Barnes said. “I should have called and asked him what I should do — sign or come back to college. He would have said, ‘Joe, where is your heart?’ Well, my heart was in playing professional baseball — and I got to pitch to Johnny Bench.”

Barnes made it to Class AA before his release after the 1967 season, but still recalls the fateful hand Ferebee never got to offer. “He didn’t have a lot to say,” Barnes said. “But what he said was worthy of being spoken.”

Vic Worry, another lefty pitcher from the late-60’s, said Ferebee was a fundamentalist who rarely strayed from the tried-and-true. “He paid meticulous attention to all details,” the Pittsburgh native said. “And he instilled confidence. When we took the field, most of the time we knew we were going to win.”

Worry, a former Class A player in the Mets’ chain, believes he’s the answer to an intriguing trivia question. “I’m the only pitcher Joe Ferebee ever took out of a game while pitching a no-hitter,” he said.

That came in 1968 against Pfeiffer rival Guilford College. Worry recorded the first out in the top of the seventh, then walked the bases loaded. “He moved me to first base,” Worry remembered. “A reliever came in and got a double play. I went back to the mound and pitched two more innings, but lost the no-hitter in the eighth. That’s the way he did things. He taught you a lesson without making a big stink.”

Several players volunteered that Ferebee had no appetite for mental lapses in the field or the batter’s box. “He wouldn’t say much about a physical error,” said Brack Bailey, Class of ’60. “But a mental error? You’d hear about it.”

Catcher Jerry Bryson was a teammate of Bailey’s who became head baseball coach at Gardner-Webb and won 305 games from 1966-80.

“They used to call me Joe Jr., because of Coach Ferebee,” he said. “He stressed fundamental play behind the plate. You learn to pitch to a situation. You get two strikes and you’re thinking becomes, ‘We’re getting this man out.’ Then it’s either coming high-and-tight or low-and-away. I learned that from him.”

So much of that is because Ferebee spoke his players’ language. Playing for him was akin to becoming a father for the first time. You knew it would change your life. You just didn’t know how much.

“I’ll tell you the most amazing thing he ever said to me,” said Gulledge, a 1968 grad and former second-baseman. “When I was older, I told him, ‘Coach, you touched my life and I thank you and love you.’ But he didn’t understand that. He didn’t think he was teaching us Life 101. To him, it was just Joe Ferebee baseball.”

And words like those don’t need to be spoken.