NFL At 100 years old: Uniforms, from bees to Color Rush

Published 8:02 pm Saturday, June 8, 2019

By Teresa M. Walker

AP Pro Football Writer

NASHVILLE, Tenn. (AP) — Tex Schramm often called Gil Brandt into his office to look at the fabric swatches draped all over his furniture, wanting another opinion on the right jersey and pants combination for the Dallas Cowboys.

He sure hit on a winning combination. Decades later, Cowboys’ jerseys remain among the NFL’s top sellers.

“The uniform thing was a special project to him,” said Brandt, now historian and player analyst for NFL.com after helping Schramm build the Cowboys. “I can’t tell you how much time I spent with him looking at these uniforms and saying, ‘Yeah, I think this is the best. This will show up the best on television.’”

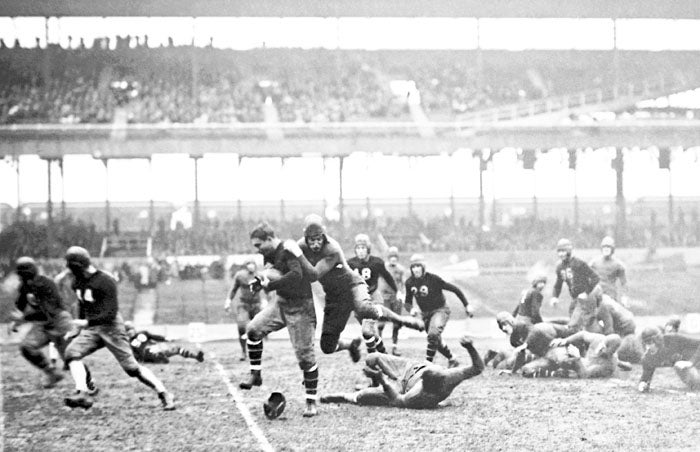

As the NFL enters its 100th season, what players wear on the field may have changed the most, going from leather helmets and long-sleeved turtlenecks and sweaters to plastic helmets with jerseys and pants almost shrink-wrapped to fit. The main reason why players wear a jersey remains unchanged even a century later: to tell who plays for which team.

“You want something to identify yourself, right?” said Jon Kendle, director of archives and football information at the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

•••

POPULAR AND ICONIC

Alphabetically, and not by order of sales, Dallas, Green Bay, Pittsburgh, Seattle and New England are the NFL teams with the best-selling jerseys over the past five years. Competing for or winning championships certainly helps popularity. And some looks are simply built to last, making for an iconic look mien the Oakland Raiders.

“When you say Raiders anywhere in the world, you think silver and black,” said Amy Trask, former Raiders chief executive officer and now an analyst with CBS Sports.

The Raiders’ look was so recognizable that owner Al Davis chose tradition when approached with the idea of pairing the black jersey with black pants or silver on silver — Color Rush years before the NFL unveiled that look in 2015. Trask says she smiled during those talks.

“He simply wasn’t interested in doing that,” Trask said. “Fair enough. His call. He was the owner. He heard us out. He listened to our presentation. He said no. And then I got in my parting words: ‘Fair enough. But then when we don’t maximize revenues in this area we can’t bemoan the fact that we’re not maximizing revenues in this area.’”

Stable ownership is a key to NFL teams keeping essentially the same look for decades. The Chicago Bears have been owned by the same family since George Halas attended the 1920 meeting where the NFL was organized, while the Packers have been publicly owned since 1923.

“They haven’t really changed the look very much,” Kendle said. “Whereas sometimes you get new owners that come in, they want to put their stamp on the organization. They want to freshen up the look, so to speak, and new uniforms or new looks that can identify that kind of change in regime.”

•••

HELPING FANS AND TEAMS

Wanting to be fan-friendly has driven other changes.

Names went on the back of jerseys in 1970. Players also chose their own numbers for decades, with quarterback Otto Graham wearing No. 60. Brandt credits Schramm and Don Weiss with devising the numbering system adopted in 1973 (and subsequently tweaked) limiting players to numbers by position. That’s why quarterbacks and specialists wear a number between one and 19.

NFL teams now have up to four uniforms, with a color and a white required for home and the road. When NFL games first hit TV, home teams wore their color uniform with the road team in white to help viewers distinguish the teams. Then Schramm wanted the Cowboys to wear white at home.

“Our explanation was that we wanted our fans to have the ability to understand what the Bears’ jerseys looked like, what the Cardinals’ jerseys looks like, what the Packers’ jerseys look like,” Brandt said. “When in reality, we did it because we thought it created an advantage for us in that they had to sit on the sunny side of the field, and we got to sit in the shade.”

Now teams, especially in the South, often wear white at home early in the season to turn up the heat on their opponents.

•••

DECORATED HEAD GEAR

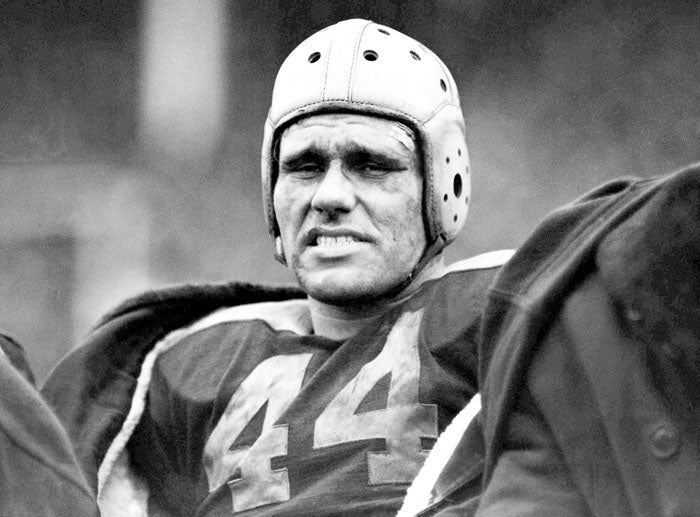

Helmets became mandatory in 1943, and Los Angeles Rams halfback Fred Gehrke painted horns on his helmet in 1948.

“That sort of spawned a whole new creation of, ‘Wait a minute. We can use this leather helmet as a canvas to represent our brand,’” said Shandon Melvin, the NFL’s creative director. “And from that point on, you started to see these things pop up, and there was much more of an interesting take on how teams would differentiate themselves.”

Pittsburgh owner Art Rooney wasn’t sure if he wanted a variation of the U.S. Steel logo on the Steelers’ helmet, so players wore it on the right side only in 1963 as a test. The Steelers went 7-4-3 that season for a rare winning record and stuck with that look. That was the same year the Raiders, who then hired Davis as coach, put their logo on the helmet as well.

Brandt credits Dallas coach Tom Landry’s wife for suggesting a star for the Cowboys’ helmet in 1960. Why? Because her husband was going to be a star.

“That’s how the star on the helmet became a reality,” Brandt said.

•••

SO MANY OPTIONS

Teams are allowed two optional uniforms with choices of an alternate color, a throwback or the Color Rush featuring one color.

Not all throwbacks are possible. The Tennessee Titans can’t wear the Columbia blue and oil derrick of the Houston Oilers because the franchise switched from white to a blue helmet with a uniform redesign in April 2018, and the NFL has a one-helmet rule. Teams like the Bears can simply strip the decal off the helmet for a classic look.

Some throwbacks didn’t work as well as others. The Steelers used a 1933 throwback with black-and-gold horizontal stripes that made them look like bees, a look switched in May 2018 for a throwback to their 1978-1979 championship teams. Jonathan Wright, the NFL’s director of uniforms and on-field product, said the Steelers loved their look and sometimes teams just want to give their fans something else.

“They’re not looking to change because they think it’s not necessarily a success,” Wright said. “They’re looking within their limitation of how many uniforms they can have to give the fans something else that they can connect to.”

The Los Angeles Chargers are going back to their past, wearing the powder blue as their primary home jersey this season. Fans have kept the jersey popular through the years, a look that Brandt says he likes the most — aside from the Cowboys.

The New York Giants did a color throwback using the NFL’s third color option in 2004. The team known as “Big Blue” actually wore red as its primary color through 1952 before switching to blue. The alternate red jerseys lasted through 2007.

•••

DON’T WEAR THAT AGAIN

Then there are perceived jinxes regarding uniforms. When Seattle lost to Chicago at home early in 2009, the Seahawks didn’t wear the neon-green jerseys again, with then-coach Jim Mora having a simple answer: “We didn’t win in them.”

Cowboys fans start moaning whenever Dallas takes the field in blue jerseys, expecting a loss. Brandt says the idea of that jinx stems from an early defeat in St. Louis. The Cardinals made their rivals wear blue jerseys and then beat Dallas. The next season, a billboard near their hotel greeted the Cowboys boasting that Dallas would be jinxed by being forced to wear blue again.

“So then that started it,” Brandt said of the rumored jinx. “And on occasion, we had everybody wanting us to wear blue jerseys on the road.”

And yes, there’s a stat for a team’s success in every uniform combination.

“Sometimes it leads to kind of these superstitious ideas,” Kendle said.

Winning can make a look very popular. The Cleveland Browns snapped a 19-game skid wearing their Color Rush look for the first time when Baker Mayfield came off the bench, leading the Browns to a 21-17 win over the Jets last September.

“Immediately that Color Rush uniform became the popular uniform for the Cleveland Browns,” Melvin said.

•••

DESIGN EVOLUTION

Today uniform changes are no longer as simple as checking fabric samples. The NFL’s creative division, first started by then-Commissioner Pete Rozelle in the 1960s, helps teams design new looks in a process that can take up to five years. Tampa Bay had the biggest redesign, switching from white and creamsicle orange with a pirate in 1996 to a waving, tattered flag with pewter and red colors in 1997. The Bucs tweaked that again in March 2014.

Melvin said owners want a uniform that will stand the test of time and be as relevant in 20 years as today. The challenge is getting fans to accept change.

“What we’ve learned is that fans are typically pretty resistant to change, and they’ll really warm up to it over the course of a few years,” Melvin said.

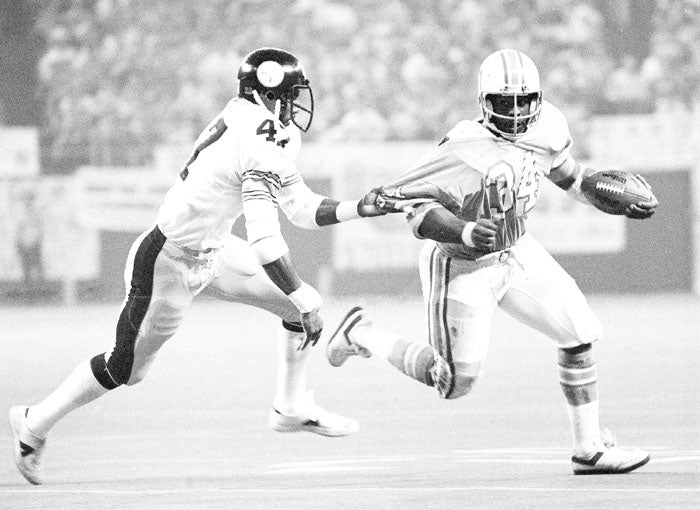

The biggest difference from a century ago may be noticed only by the players themselves — and the equipment staff. Wool and cotton were the materials of choice for years, in turtlenecks and sweaters to more modern jerseys. The development of nylons and polyesters, whisking away sweat without becoming heavy, now allows designers to leave little for defenders to grab, unlike the 1970s when Earl Campbell often lost pieces of his jersey.

Wright said to credit Nike for reducing the number of seams in today’s uniform, from 21 individual pieces of fabric sewn together for a jersey and pair of pants a few years ago now down to approximately five.

“You’d be surprised at how impactful that is from a weight standpoint, from a strength and tenacity standpoint,” Wright said. “That’s a game changer that doesn’t really get a lot of credit.”

With TV going from black and white past high-definition to 4K, expect NFL uniforms to grow beyond the numbers, name and logo.

“It’s allowing us to put details in and textures and materials into things that wouldn’t have been seen by most fans years before,” Melvin said. “So we were trying to take advantage of that opportunity where we can.”

___

AP Pro Football Writer Josh Dubow and AP Sports Writers Tim Booth, Greg Beacham, Joe Reedy and Tom Canavan contributed to this report.