‘No one woke up one day wanting this life’: Syringe exchange program one strategy to abate opioid epidemic

Published 12:02 am Sunday, September 1, 2019

By Elizabeth Cook

For the Salisbury Post

KANNAPOLIS — Sticky notes cover a bulletin board at the Cabarrus Health Alliance, sharing reactions from users of the agency’s free syringe exchange program:

“Being more cautious,” says one note.

“Making sure that others around me use clean needles …,” says another.

“I no longer use a needle until the numbers are gone,” says a third.

And then there’s this: “I know three people who wouldn’t be alive if it wasn’t for this place.”

Since opening in June 2017, the syringe exchange program at Cabarrus Health Alliance has given sterile syringes and other material to more than 500 people, a majority of them from Rowan County.

Now it’s one of about 30 such programs across the state, and Rowan may eventually offer the same service as another strategy to abate the opioid epidemic and help people who are addicted.

“This is really the first step that they’re taking to control their health,” says Marcella Beam, executive director of Healthy Cabarrus.

Using the same needle over and over — or sharing needles with someone else — can cause infection and disease.

To date, the Cabarrus program has collected more than 67,000 used needles and given out 233,023 sterile needles.

To outsiders the program may appear to perpetuate drug abuse, but to users it can be a lifeline — a means of protecting themselves from disease as they grapple with their addiction. The program is also a sign that someone recognizes their situation, Beam says.

“We as a community need to understand that no one woke up one day wanting this life for themselves,” she says. “There’s a lot of trauma for individuals enrolled in the program, a lot of life experiences that those of us who are not in active addiction may not understand.”

Drugs can be an escape or a coping mechanism, she says.

“The more we learn as a community on being compassionate and understanding, the more support we can provide to individuals who are wanting to get into recovery,” she says.

Opioids continue to take a toll on North Carolina communities, with nearly 2,000 people in the state dying of opioid-related overdoses in 2017. The rate of N.C. opioid overdose deaths — 19.8 per 100,000 — exceeds the national rate of 14.6.

Nina Oliver, director of Public Health for Rowan County, supports having a syringe exchange program in Rowan.

“I am a major proponent for syringe exchange programs, as they help prevent infectious diseases that can cost thousands of dollars to treat and increase the likelihood of the user going into treatment,” Oliver says.

Treating someone for HIV/AIDS or hepatitis C —a liver-damaging virus that can lead to cirrhosis, cancer and death — can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Meanwhile, the sterile syringe that could prevent transmission costs only about 7 cents, according to Oliver.

N.C. taxpayers paid $50 million for hepatitis C treatment and $117 million for HIV treatment in 2014, according to Oliver.

• • •

Each month, about 130 people go to the needle exchange clinic in the Cabarrus Health Alliance building at 300 Mooresville Road, across the street from the Kannapolis Police Department.

First-timers fill out an intake form with their name and answers to questions about their living situations, the drugs they use and and injection habits. Then they’re given a client ID number on a card to use when they return.

So far, participants have come from Cabarrus, Rowan, Stanly, Mecklenburg, Union and Davie counties.

“We don’t restrict,” Beam says.

Since September 2018, the program has had 484 interactions with Cabarrus participants and 819 interactions with participants from Rowan, she says.

The program other items used for injecting drugs — alcohol prep pads, sterile water, bits of cotton and a clean cooker —in addition to fresh syringes and needles. It also distributes free naloxone kits to reverse overdoses, condoms and other prophylactics to prevent pregnancy and the spread of sexually transmitted diseases.

Participants may receive a container for disposing of their used needles or “sharps.”

If they need food, participants can get canned goods from the Blessing Box that a Boy Scout built outside the clinic as his Eagle project.

People can be tested for sexually transmitted diseases, HIV/AIDS and hepatitis in the building, too.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, acute hepatitis C cases reported to CDC more than tripled from 2010 to 2016, with most new infections due to increased injection drug use associated with the opioid crisis.

• • •

Program participants can also talk to someone who is there to help,.

“We want this to be a safe space and a non-judgmental space, and to be here as a set of ears,” says Kristin Klinglesmith, a substance use public health educator. “We don’t tell them what they need to do. We just help guide them when they ask.”

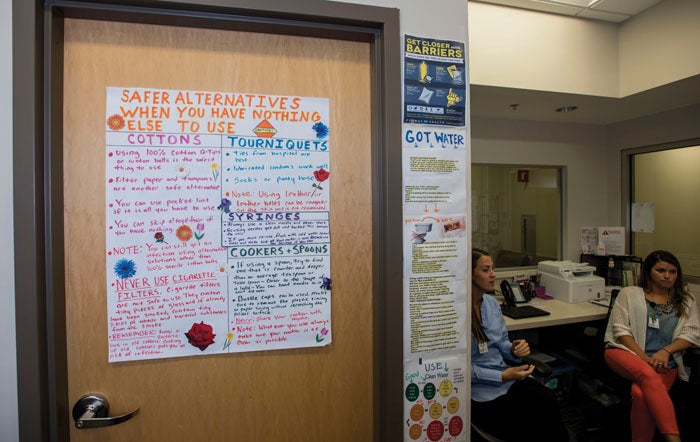

Signs on the walls give tips on such things as how to treat abscesses, where to get clean water in a pinch (toilet tanks, not toilet bowls) and the best places to inject drugs (arms and legs, not the neck).

Some participants go in and out quickly, getting what they need without any conversation.

“Then there are some people who we have built really strong relationships with and they’ll sit down and talk with us for a long time,” Beam says.

That can open the door to discussions about testing or treatment.

“Our role here really is harm reduction,” Beam says. “We’re reducing the harm they’re potentially (inflicting) on themselves or others in regards to disposing their needles properly rather than throwing them out a car window.

“Once they’re ready for that next step, we’re equipped to direct them and engage them with someone who can guide that process.”

• • •

For years, syringe exchange programs were illegal in North Carolina. When the legislature lifted the ban in 2016, people at the Cabarrus Health Alliance set to work. A community donation funded the program initially — a gift from a person whose brother fatally overdosed.

The program has relied on a patchwork of grants since then. Just this summer, the state lifted the ban on using state funds for their supplies.

Beam estimates it costs about $175,000 a year to run the program with two staff members. Lately, volunteers have staffed the clinic.

Before it started, organizers consulted with community partners in law enforcement, emergency services and other fields, seeking their approval or acknowledgment, according to Beam.

“I would’t say that all of them were huge advocates and big supporters, but they understood from a public health perspective the impact that a program like this has,” she says.

She’s heard people question the wisdom of giving out naloxone.

“I always ask people to consider if it’s their child or their family member,” Beam says. ” I wouldn’t want to take a lifesaving drug from someone in that situation.”

When Klinglesmith gives programs on the needle exchange to civic groups, she says, people are more curious than critical, and they seem reassured when they hear the program is both cost-effective and evidence-based.

According to the CDC, a review of 15 studies found that needle exchange programs were associated with decreases in the prevalence of HIV and hepatitis C and decreases in the incidence of HIV.

The number of newly diagnosed HIV infections in Rowan and Cabarrus has been declining. In Rowan, cases fell from 19 in 2016 to 13 in 2018. In Cabarrus, the cases fell from 25 in 2016 to 15 in 2018, according to data from the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services.

• • •

One benefit of the program has been fewer calls to 911 for overdoses. In Cabarrus County, that number peaked at 81 in August of 2017. The widespread availability of naloxone kits helps friends and family treat an overdose, rather than dial 911.

While the needle exchange program efficiently distributes naloxone and clean syringes, solutions to addiction — long-term treatment and recovery — are harder to come by.

Daymark has a 16-bed facility that offers mental health and substance use related treatment, but the maximum stay is three to seven days. That gives someone time to get the drugs out of their system — to detox — but not to truly enter recovery.

“Detox is just one piece of the recovery puzzle,” Klinglesmith says. “There may be a misconception out there that once a person is detoxed and they’re no longer physically dependent, that that’s it, and that’s not the case at all.”

Long term facilities that offer 30-, 60- and 90-day addiction treatment are found in other parts of the state, but many have waiting lists. Then there’s the cost factor.

Staff at the clinic have seen clients go through detox and not be able to get a bed in a long-term facility or have to wait for that bed. In the meantime, they go home to the same environment where they had been using drugs.

“And we’re wondering why they’re not cured,” Beam says.

Many of the clients who come in got started on painkillers prescribed for a back injury from work or injuries from a traffic accident, she says. They started out doing what they were supposed to do and gradually maxed out what doctors would prescribe. So they turned to opiates on the street to ward of “dope sickness” and feel OK.

“The saddest thing is when they’re ashamed to come in,” Beam says. “You’re heartbroken for them. They don’t know what else to do. They’ll say ‘I’m embarrassed.

“We always try and reaffirm them and say no, you’ve made a great step. … We’re the first place you can make a step toward improving your health; you’re getting back control.”