Atwood offers a balm to Gilead

Published 12:00 am Thursday, October 10, 2019

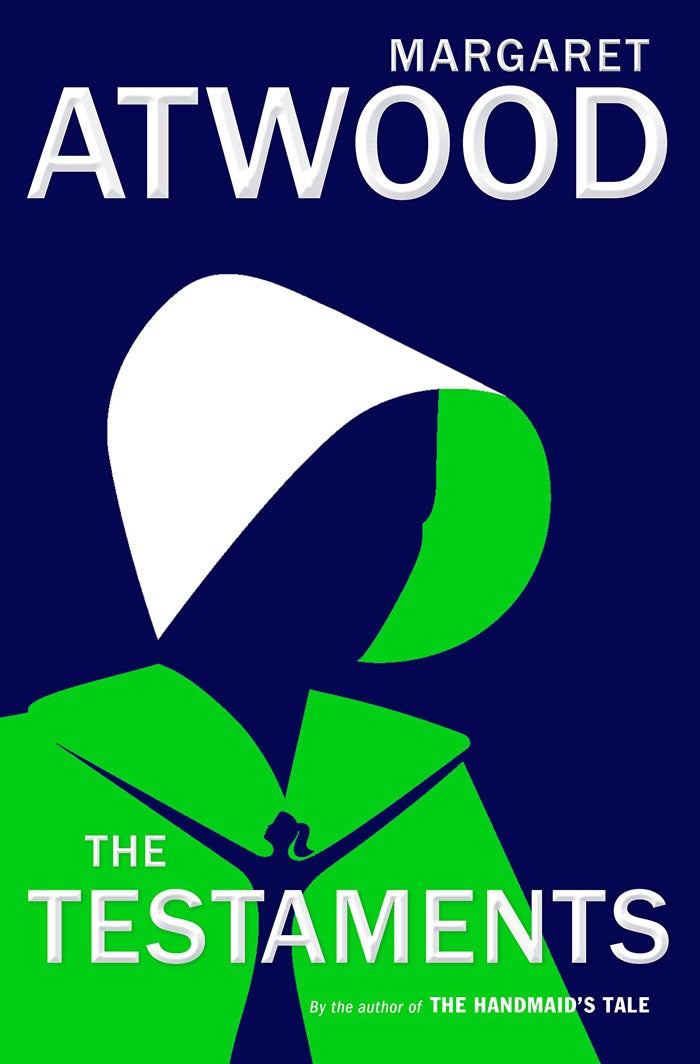

“The Testaments,” by Margaret Atwood. Nan A. Talese. New York. 2019. 432 pp.

By Deirdre Parker Smith

deirdre.smith@salisburypost.com

In “The Testaments,” the perhaps unforeseen sequel to the jarring and all-too-topical 1985 novel, “The Handmaid’s Tale,” shows us Gilead at its worst, rotting, as Aunt Lydia describes, its principles and precepts tarnishing, and its birth rate plummeting.

Margaret Atwood has ends she wanted tying up. She has ideas about the future, which are less grim than “Handmaid’s” would have lead you to believe.

She maintains the society where women are merely tools for pleasure and procreation. In Gilead, wives are as expendable as toothpicks, and handmaids a lower, but necessary class, expected to produce viable children.

Atwood tells this story in the past tense, using three narrators — Aunt Lydia, secretly scratching out her memoirs, Agnes, a young woman raised in Gilead and being trained to be a wife, and Daisy, a young woman outside Gilead, who has a vital connection that could save or ruin it.

The testaments come from Agnes and Daisy, giving testimony about what happened to them in and outside of Gilead, and Aunt Lydia’s revelations, that will damn her or damn Gilead. It’s still a tightly closed society, with a perverted faith in God. Men are in charge. Women have no rights, except the Aunts, who are meant to manage the wives, handmaids, adolescent girls, and, secretly, the Commanders, who have no clue how powerful a woman can be.

It’s been 34 years since Atwood last peered into Gilead, 15 years into Gilead’s future after June escaped.

As oddly prophetic as the first novel was, this novel is still frightening, but with a light at the end of the tunnel.

Reaching that light will require bloodshed, lies too numerous to count, subterfuges, conspiracy, murder.

This time, Aunt Lydia gets a gruesome back story. A former judge outside Gilead, Aunt Lydia knew how to wield power. Gilead kidnaps and breaks her, but she still knows how to get what she wants, and isn’t afraid to use any and everyone. Trust no one. Play rivals against each other. Bow and scrape to the right people. Stand in the firing squad to execute your colleague. The name of the game is survival.

Agnes lives in the house of the powerful Commander Judd, happy with her “mother,” Tabitha. who sickens and dies. The replacement wife, Paula, is a wicked stepmother. The sooner she can get Agnes married off, the better.

Judd is a powerful commander, one who uses and trusts Aunt Lydia, to a point. She reveals useful secrets to him, furthers her own plots with his unwitting help.

Outside Gilead, and it’s hard to fully picture the boundaries, lives Daisy, Nick and Melanie. They run a thrift shop while Daisy goes to school, where she learns about the awful Gilead.

Nick and Melanie keep a close eye on her at all times, and Daisy doesn’t ask many questions about the comings and goings at the thrift store.

You’ll suspect who Daisy really is long before a crisis strikes and the plans of the Mayday group have to be accelerated.

Meanwhile, signs of decay in Gilead’s armor of self-righteousness are showing. Aunt Lydia has become so powerful, a poorly-executed statue of her stands outside Ardua Hall.

The Commanders are demanding younger and younger wives, girls in their early teens; and a respected dentist in Gilead is revealed to be a pedophile. Unbirths, as they are called, are more frequents, along with alarming deformities.

Atwood details the process of Particicutions, in which handmaids rip a convicted man to pieces with their bare hands.

We get to know Agnes and her friends, Becka and Shunammite, each with a different dream. As disgusting as women are, according to this society, being with a man is even more disgusting.

While the plots inside and outside of Gilead ferment, readers will begin to wonder about the outcome. Could it be that Atwood has some idea of redemption? Or will the perversity of this misguided society prevail?

As in “Handmaid’s Tale,” Atwood is spare with her descriptions of Gilead, beyond the societal ills. Women are chattel, their opportunities non-existent, but what lies beyond the neatly furnished houses and frightening spectacle of the arena?

Limiting the spectrum helps create the isolated feeling of Gilead; the lack of inner thought makes sense, when thought is dangerous. Atwood’s writing is straightforward, sparse, declarative. The plot is tight, with all points leading to the main focus.

“The Testaments,” for its anger, Aunt Lydia’s steely will and the girls’ fear, is somewhat unemotional at the same time. The book has a purpose. The story has a meaning it fairly shouts, told with a cold, hard line.

Read it and ponder how our modern society reflects Gilead; how women’s choices are still forced upon them, and how not just women, but so many others, are subjugated to people in power.