My turn, Virginia L. Summey: Why ‘Fame’ needs to go

Published 12:00 am Sunday, June 14, 2020

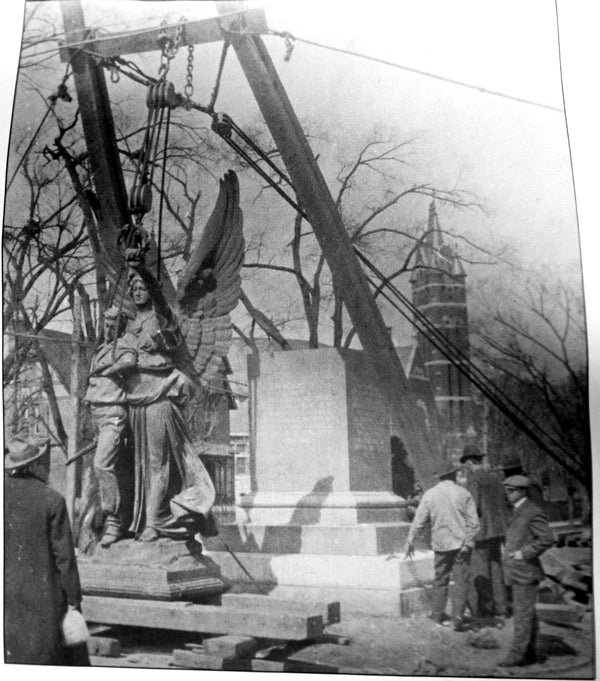

- This undated image shows the "Fame" Confederate monument being raised to its pedestal.

By Virginia L. Summey

On May 10, 1909, “Fame” was dedicated in downtown Salisbury. These sorts of dedications were a common affair in the South at the time. Indeed, the erection of “Fame” in Salisbury was part of a larger trend in the former Confederate states. But after the killing of George Floyd and other African Americans at the hands of police, “Fame” only amplifies the systemic racism imbedded in our culture.

After 111 years, it is time for “Fame” to go.

To understand why “Fame” needs to be removed, it is important to understand the context under which it was erected. The year 1909 came in the midst of the Jim Crow period of segregation in the South, which lasted roughly between the years 1898 and 1954, implementing a new form of racial hierarchy designed to emulate the pre-war South. The old adage goes, “The North won the war, but the South won the peace.”

As part of “Winning the peace” a Lost Cause narrative portraying the former Confederacy as having fought a moral battle for state’s rights (a euphemism for defending slavery) and commemorating those who fought on its behalf. In North Carolina, it also involved the white supremacy campaign from 1896 to 1900, which included the successful coup d’etat in Wilmington in 1898 in which white supremacists took over the city at gun point, killing as many as 300 African-American citizens on the way. The white supremacy campaign also included the disenfranchisement of African Americans with a grandfather clause in 1900, and the disproportionate policing of black bodies by legal and extralegal measures. Nowhere is this more evident than in the 1906 lynching of three African-American men in Salisbury.

“Fame” was erected in the aftermath of North Carolina’s white supremacy campaign. During Jim Crow, various Confederate memorial associations primarily comprised of the white, elite South raised funds for monuments to commemorate Confederate soldiers. The goal was memorialize their antebellum past: a time when race, in addition to their class, determined their social worth and their economy was built on agriculture cultivated by the commodification of human beings. Men gave their lives to preserve it.

In the 50 years after the Civil War, white southerners still lamented the devastation of their slave-based economy and social structure. The Confederate monuments, meant to honor the men who fought to protect simpler times the white elite longed for, also served as a celebration that the goals of Jim Crow had been realized: African Americans still lived on the lowest rung of southern society.

“Fame” is not different from other Confederate memorials across the South. The dedication speeches of these statues made references to the Lost Cause or white supremacy, and they were all single-race affairs. At the dedication of “Fame,” Confederate General Bennet H. Young, of Kentucky, spoke, saying the South was “defeated, not because they were wrong or unfaithful in any aspect whatever, but because an overruling Providence decreed their downfall …” It was important for the elite to believe that even though they lost the Civil War, it had nothing to do with America’s original sin – slavery.

The United Daughters of the Confederacy was the driving force behind “Fame.” Established in 1894, the purpose of the UDC was to memorialize and exonerate their Confederate ancestors after their defeat. According to UNC-Charlotte historian Dr. Karen L. Cox the UDC “aspired to transform military defeat into a political and cultural victory, where state’s rights and white supremacy remained intact.” They were extraordinarily successful, and monuments are one of their longest-lasting contributions to the Lost Cause. They serve as constant reminders of a country that never was, and a war that fundamentally – and permanently – changed the South they wanted to preserve.

Today, these monuments are symbols of polarization between one group, who feels it honors their ancestors, and another for whom it serves as a reminder of the enslavement of theirs. But as we see from the May 31st arrest of Jeffrey Alan Long, a neo-Confederate who fired a gun by the statue, these monuments are increasingly magnets for hate.

Across the South these monuments are being removed in an effort to move towards a more equitable future for all Americans. Of course, removing monuments will not solve the deeply entrenched issues of systemic racism in the United States. But moving “Fame” will send a signal that Salisbury is not a city that honors the worst parts of the past, but one willing to move into a better future for all its citizens.

Virginia Summey grew up in Salisbury and graduated from East Rowan. She received her bachelor’s degree from Catawba College. Most recently, she received her doctorate in U.S. history from the University of North Carolina in Greensboro, where she currently teaches.