Josh Bergeron: Keep local elections unlike national politics

Published 12:05 am Sunday, January 24, 2021

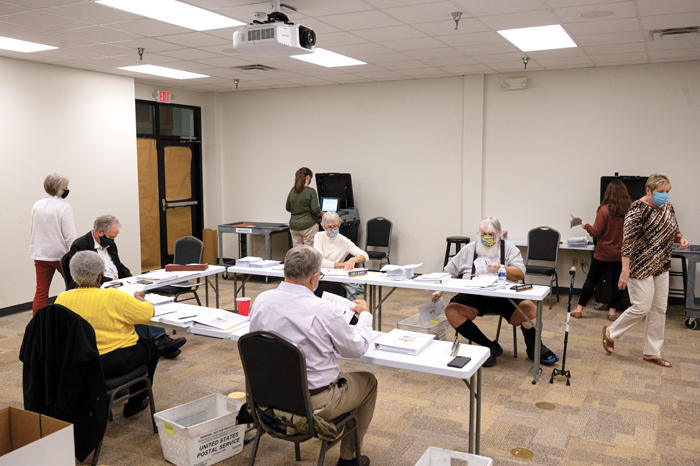

- Josh Bergeron / Salisbury Post - Members of the Rowan Countuy Board of Elections after the 2020 election review ballots at tables while staff members feed ballots deemed OK into tabulators.

More than two months ago, on Nov. 8, an Associated Press story on the front page of the Post reported that now-President Joe Biden had secured enough votes to be declared the winner of the 2020 presidential election.

With the political climate of the country at the time, I expected to receive phone calls and emails the next day. Biden hadn’t won the presidency, the readers would say. And, even if he had, Biden had won a fraudulent election, I expected to hear.

The calls did come. So did a few emails and an anonymous letter or two. People who were not ready to accept the results made it known. I will freely admit that national outlets, including the Associated Press, tend to get overzealous at times with inserting opinion into news stories. But the fact that the country had a new president was exactly that — a fact.

In the two months that followed the November election, there were all manner of mainstream conspiracy theories about voting machines, foreign countries (sometimes multiple) having a role in our country’s elections, sharpie markers, bags or suitcases of ballots and too many others to name.

They marked a terrifying turn down a slippery, dark path away from usual election security talk.

North Carolina isn’t entirely unfamiliar with talk about election fraud. In 2016, the state’s outgoing governor, Pat McCrory, alleged voter fraud in 50 of the state’s counties and targeted some individual voters, too. After 2018, the 9th District Congressional election required a do-over because of an illegal ballot harvesting scheme that raised doubts about the narrow victory of Mark Harris, a Republican who chose not to run again after the scheme was unveiled.

But fraud allegations were most troubling in 2020 and 2021 because elected officials and people who successfully campaigned for office raised troubling theories that the basic mechanics of elections were corrupt or had been compromised and held onto their claims even as courts repeatedly tossed out lawsuits. Even worse, the theories were validated by others who made vague claims like, “People are raising a lot of questions about the election.” If politicians truly believe what they said, the public deserves a wave of bills that provide new election security without discriminating as well as new funding for local governments to improve the security of elections.

For the sake of democracy, North Carolina and its election officials are lucky the state voted for former President Donald Trump instead of Biden or it might have also been the subject of conspiracies. The Rowan County Board of Elections, an office that strives to administer elections in a nonpartisan manner, was already the victim of novel criticism because of the divisive atmosphere in 2020. The use of voting machines popular in conspiracy theories and/or North Carolina going for Biden would have made things significantly worse.

The national news cycle has mostly moved on from election conspiracies because Biden was sworn in as the nation’s 46th president last week. But it’s worth pausing for another moment to say that cooler heads must prevail in future elections, including local ones. That election fraud allegations reached a new height this year poses worrisome potential for how down-ballot races might be affected.

Consider a future where Rowan County’s demographics have shifted enough that Democrats or any other party has a 50-50 chance of being elected to countywide office (a future possible if growth from Charlotte also means changes in political persuasions). In a race where a candidate wins by a minuscule margin it’s now entirely possible that a conspiracy theory emerges unchecked on social media and goes mainstream, prompting candidates and their representatives to press the elections officials for action.

There are some safeguards in place to ensure winning candidates take office, including deadlines for certification and dates enshrined in ordinances. Rowan County, for example, outlines the first Monday in December as the day when winning candidates take office.

Another factor: Compared to national or statewide races, there’s generally not large amounts of power or money involved in winning local elections. Some weeks, county commissioners, mayors and council members find themselves working the equivalent of a full-time job, fielding criticism and threats and making relatively little in compensation. State legislators certainly find themselves working the equivalent of a full-time job and do not earn nearly enough to live comfortably from legislating alone.

Still, a certain degree of humility and civility is required to bring elections to an end. More so in local races than in national or statewide ones, there’s weight to whether a majority of the electorate thinks it’s over. Local candidates still have to live in a community they’re elected to represent, and it’s not very pleasant if all of the person’s neighbors think he or she has gone off the deep end.

One solution to keeping local elections unlike national ones is to embrace positive politics and compromise and find candidates who work to lift people up rather than tear them down. Opt for candidates with a strong sense of ethics and a moral code, regardless of their partisan affiliation.

Voters also must work to be more informed about voting and the processes that make elections work as well as seek out multiple sources of information when possible, particularly about stories that seem too good, or too bad, to be true. A good way to get started is by volunteering in an election, whether it’s for the Rowan County Board of Elections, a political party or partisan or nonpartisan organization.

Josh Bergeron is editor of the Salisbury Post.