World War II veteran, longtime Rowan County farmer, celebrates 100th birthday

Published 12:00 am Sunday, October 17, 2021

MOORESVILLE — After allied forces stormed the beaches of Normandy and started pushing east, Hoke Karriker was fighting for his life in a small town nestled against the Rhine River occupied by German troops.

Hoke, raised in southern Rowan County, was one of 18 men in a patrol charged with flushing the German soldiers from the town. During the ensuing skirmish, 16 of the men in Hoke’s company were killed. Hoke and the only other lucky survivor were forced to hide from enemy fire in foxholes and scamper through homes and gardens to survive.

The two soldiers eventually made it to safety. The harrowing experience was the first of many close combat encounters Hoke experienced on the front lines during World War II.

Despite coming close to death multiple times, Hoke survived the war and returned home to Rowan County in 1946. On Saturday at Concordia Lutheran Church, Hoke was surrounded by friends and family as he celebrated his 100th birthday one day early.

Living for a century might seem like a major accomplishment to some, but Hoke said the special occasion is “just another day.”

“If the lord led me to be 100, I guess I’ll go ahead and do what I’ve been doing if that’s what he wants me to do,” Hoke said.

Hoke was born on Oct. 17, 1921 in west-central Rowan County, near the Bear Poplar community, and was the first son in a farming family. His family moved to China Grove when he was six years old, where Hoke delivered The Charlotte Observer to readers around town while saving money for a bike.

When Hoke was in eighth grade, his family moved to a farm outside of China Grove and Hoke spent his teenage years oscillating between high school and working long hours raising cotton, sweet potatoes and corn. Hoke left school at 17-years-old and started working in the cutting department at Cannon Mills.

Despite the looming threat of world war, Hoke married Dorothy Frieze Bost in 1940. Their first two children, Ferman and Johnny, were born in 1941 and 1942. As he and Dorothy transitioned to life as sharecroppers, the U.S. entered the global conflict. Hoke was of draft age, but he was initially deferred because of his two children.

Hoke wasn’t exempt from military service for long. On his fourth wedding anniversary in 1944, Hoke received notice that he’d been drafted in the Army infantry.

After basic training at Camp Wheeler in Georgia, Hoke was loaded onto the British ocean liner the Queen Elizabeth. On his journey across the Atlantic, the captain steered the cruise liner in a zigzag pattern to avoid the threat of submarines lurking underwater.

“He changed course every four or five minutes so they couldn’t torpedo the ship,” Hoke said.

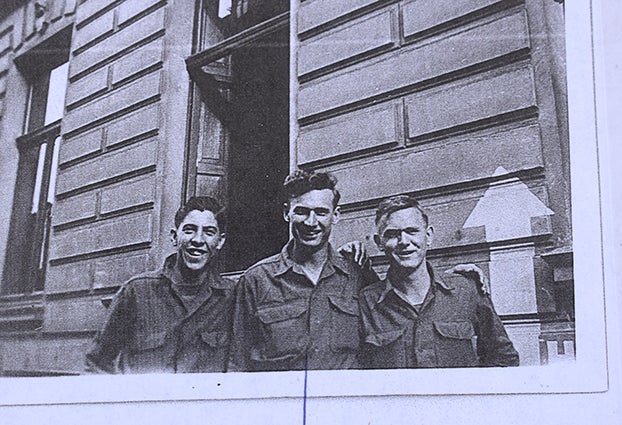

When Hoke arrived in Europe, he joined the same squad as his brother, Paul Leonard Karriker, and fought retreating German forces across France and into their home country. Hoke experienced plenty of grisly action during the months he spent on the front lines.

While crossing a river in a small boat, Hoke was forced to jump into the water to avoid enemy fire. In hastily built foxholes, Hoke saw his fellow soldiers killed by enemy fire but also by taking their own lives. Even after Germany surrendered, Hoke witnessed a hanging of a Germany sympathizer in Czechoslovakia while waiting to return to America.

Throughout it all, Hoke kept a small Bible in his breast pocket and read it when he could. He also sent his pay back home to Dorothy, intending to use the savings to purchase a farm when he returned.

Hoke was processed out of the Army and came back to America on a liberty ship that traversed the North Atlantic route. The ride home, Hoke said, was significantly rougher than the ride to Europe — even though there wasn’t the threat of being torpedoed. By the end of the trip, Hoke said most of the troops were seasick from the jostling waves. He was one of the few who wasn’t.

“I reckon I was tougher than most of them,” Hoke said.

On Feb. 6, 1946, Hoke arrived at his father’s house, just in time to surprise his family during Sunday lunch.

“I got home and they were eating Sunday lunch and they all broke up when I went in,” Hoke said. “I walked in on them and they didn’t know I was coming.”

Johnny, only about 2-years-old at the time, said his father returning from war was one of his first major life memories, and a joyous one at that.

Using the funds he’d saved during combat, Hoke purchased a piece of property along Corriher Grange Road in southwest Rowan County that had a livable house, small log barn and corn crib.

Hoke picked up farming again almost immediately, but had to readjust to society in other ways. While delivering a shipment of sweet potatoes to a wholesale produce distributor in Charlotte, Hoke was flabbergasted when he encountered a one-way road for the first time.

He and his wife both started working at Cannon Mills, with his second shift schedule allowing him time to milk a growing herd of dairy cows in the morning. During his working life, Hoke and his family continued to operate their property as a working farm, raising crops, dairy and beef cattle, pigs and more.

The Karriker family found success raising the Percheron breed of draft horses. Hoke took their best steeds to horse shows throughout the Southeast and Midwest. A horse named Dan II even claimed the blue ribbon at a show in Winston-Salem.

Hoke joined the Corriher Grange and served as president and vice president of the organization several times. He was recognized one year as Granger of the Year for North Carolina.

Around the time Hoke’s daughter, Vinnie, was born in 1954, he began working at a missile production plant operated by Douglas Aircraft Company for the U.S. Army. The facility is where Nike Ajax and Nike Hercules surface-to-air missiles were produced. Hoke was in charge of the shipping department, which made him the man who knew where the dangerous weapons were sent.

During his time at the plant, Hoke accidentally drove a nail into his finger while packaging missiles. The same toughness that helped him endure the war came in handy once again and Hoke merely bandaged the wound and kept working.

“You don’t stop for injuries unless you’re half dead,” Hoke said.

When the missile plant closed, Hoke was presented with the option of moving to California or Oklahoma to continue working for Douglas Aircraft. He turned the offers down.

“I didn’t want to leave home,” Hoke said.

Hoke went on to work at the postal distribution center in Charlotte until he retired. He remembers sharing the bounty of produce harvested from his garden with his fellow coworkers at the postal distribution center.

Each of Hoke’s four children moved away from the property for a time. Ferman forged a career as a graphic artist in Charlotte, Johnny spent over three decades as an administrator and professor in the community college system, Vinnie worked as a clinical research trial coordinator at UNC Chapel Hill for 30 years and Katrina, the youngest, works for Henkel.

Although each of the children left Rowan County, they have all returned and now live at Karrimont Farm, the piece of land Hoke purchased with his war savings and which still produces beef cattle, meat goats and a variety of crops.

“This is home,” Vinnie said. “This is where you want to be.”

Hoke has 11 grandchildren, 18 great-grandchildren and four great-great-grandchildren, 1 step-grandchild and 7 step-great-grandchildren.

He and Dorothy celebrated 62 wedding anniversaries before she passed away in 2003.

Even as he crosses the century mark, Hoke continues to walk a mile everyday (weather permitting). A voracious reader, Hoke also finishes about 20 books a week.