Catawba grad Dave Robbins gets the call to the Hall

Published 12:00 am Sunday, January 30, 2022

By Mike London

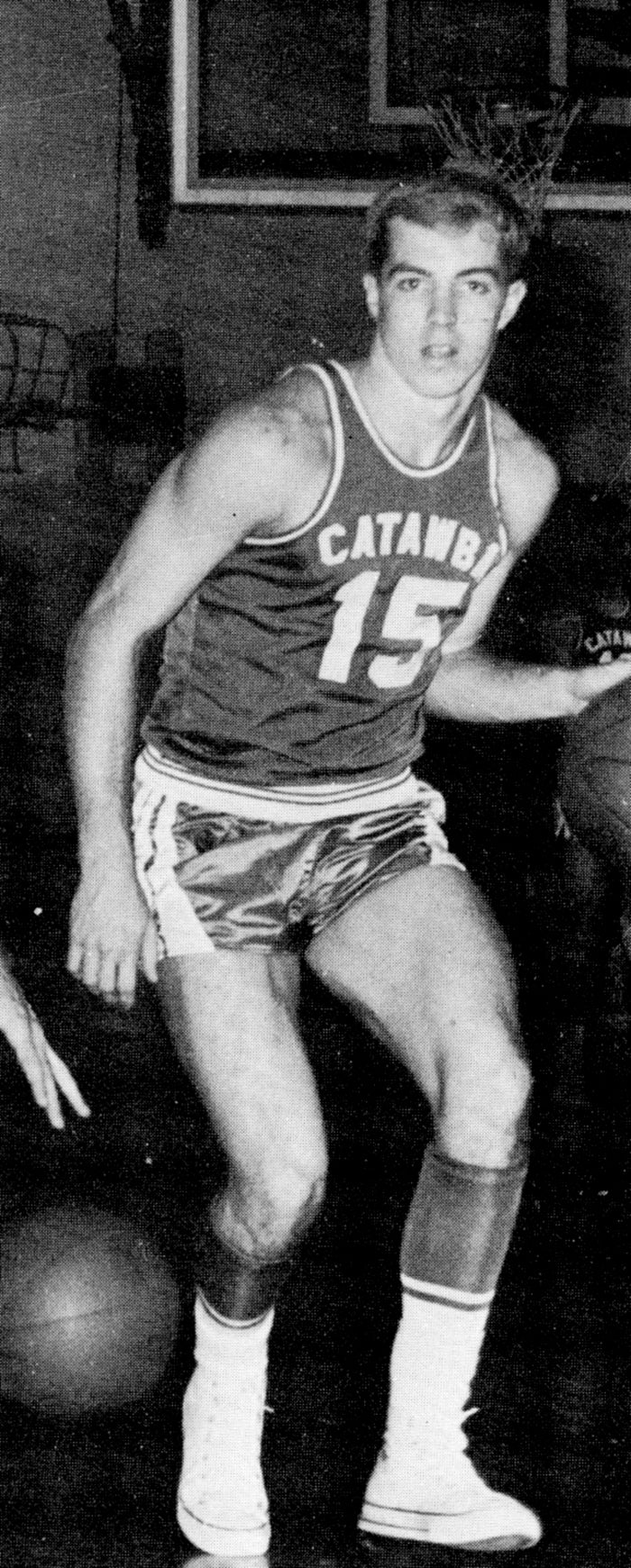

- Dave Robbins from his Catawba College playing days.

By Mike London

mike.london@salisburypost.com

SALISBURY — Charles Oakley played 19 seasons in the NBA as the textbook, 6-foot-8 power forward/enforcer.

Oakley wasn’t fined a single time in his pro career for being late, not even for a practice. The reason for that can be traced to a 1966 Catawba College graduate named Dave Robbins.

Robbins is part of the recently announced North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame Class of 2022. While he was a marvelous pass-catcher for Catawba football back in the day, he has been inducted into a long list of halls of fame because of the 30 seasons he coached men’s basketball in Richmond at Virginia Union University. Robbins is white, so he had unique experiences as the first white head coach in the CIAA, a D-II conference filled with drama and history.

It was at Virginia Union that Robbins’ path intersected with Oakley’s.

Robbins coached 713 wins and three Division II national champions at Virginia Union (1980, 1992, 2005). There also was a runner-up season in 2006 and three more Final Fours in 1991, 1996 and 1998.

An Oakley-led Virginia Union team in 1985 went 31-1, with the loss coming on a last-second miracle by Winston-Salem State.

Oakley arrived on the Virginia Union campus in 1981.

“He was from Cleveland, and he came in for a recruiting visit wearing a fur coat,” Robbins said. “Fortunately, we were having a heat wave in Richmond, so he went from 18 degrees to 81 degrees, and he loved the weather, That helped us some. When I sat down with his mom, she’d been hearing a lot of promises from a lot of people. I didn’t make any promises. I just told her that if Charles came to Virginia Union, he’d have a chance to become a grown man.”

That’s what she wanted to hear.

Oakley’s mother asked if Charles would have a roommate.

“No ma’am, he’ll have two,” Robbins told her.

With work-study financial aid, Oakley got a full ride.

He earned it. He was the best player Robbins ever coached.

As a senior at Virginia Union in 1984-85, Oakley was a monster. He averaged 24.3 points and 17.3 rebounds per game.

“We’re getting ready to leave on a road trip one day, and Oakley’s late,” Robbins said. “So I go back to my office, call my wife, tried to waste five minutes or so, and by the time I get back to the bus, Oakley has shown up, and I breathe a sigh of relief.”

He called Oakley into his office when the team returned home.

“I told him, ‘Charles, you do that again, and I’m leaving you.’ Oak laughs, and says, ‘Yeah, right, Coach. I’m getting 24 and 18. No way you’re leaving me.'”

Not long after that, that Virginia Union players were boarding the bus to make the long trip to Salisbury to play the Livingstone Blue Bears.

Departure time arrived. Oakley was nowhere in sight.

“Let’s go,” Robbins told the driver.

Robbins heard murmuring after a few miles on the road. Players knew that at any second, the bus would be turning around and returning to the school to find Oakley.

The bus began rolling down Interstate 95. Players were still certain Oakley wouldn’t be left behind.

“Well, about the time we get to Raleigh, they’re finally convinced we’re not going back to get Oakley,” Robbins said. “One of the guys said, ‘Dang, he’s left Oak.'”

Virginia Union played Livingstone without Oakley. Jamie Waller, who would also make it to the NBA, stepped in for Oakley, had a huge game and led the Panthers to victory.

Oakley wasn’t late again — ever.

Years later, after he’d made it in the NBA, Oakley came back to Richmond, wearing a three-piece suit, and addressed the Virginia Union team. He told the story about how Robbins had left him, and the team had won without him. Lesson learned.

Oakley and Robbins were close and are still close. They always called each other “Big Fella,” even though Oakley is nine inches taller than the 5-foot-11 Robbins.

Oakley, whose mother was from Alabama, would help Robbins recruit the second-best player he ever had. That was Ben Wallace, who was from a small town in Alabama and attended a summer camp in Alabama hosted by Oakley.

“I used to call Oak and ask him if he liked a player I was hearing a lot about, and he’d always tell me, ‘Nah, he can’t play.’ But then one day Oak calls me and he says he’s got a player for me. I asked him if it was a big man, and he said, ‘He’s not that big. But he’s a man.'”

Robbins took Wallace without ever seeing him play.

“I never doubted,” Robbins said. “If Oak said a guy could play, I knew he could play.”

Wallace played two years of junior college ball at Cuyahoga Community College near Cleveland before arriving at Virginia Union, but he blocked more than 200 shots in the two seasons he played for Robbins.

Wallace would lead the NBA in rebounding twice and in blocked shots once.

Robbins grew up in Gastonia and went to Ashley High school, a school that would later merge with Holbrook High to form Ashbrook. He played basketball for coach Larry Rhodes, a North Carolina coaching legend. Robbins excelled in basketball, football and track and field in high school, but his grades left something to be desired.

“My mother said that I had no thirst for knowledge,” Robbins said.

Prep school at Oak Ridge was necessary to boost his grades, and he caught a break when Catawba basketball coach Sam Moir got to see the shooting guard shine f0r Oak Ridge against the Catawba jayvees.

Robbins spent 2 1/2 years at Catawba.

He was part of track and field champions.

His basketball accomplishments were modest. His greatest contribution may have been providing the opposition for legend Dwight Durante, when Durante was working out for the Indians.

“I’d always thought I was pretty quick — up until then,” Robbins said.

Robbins also got to defend against Western Carolina phenom Henry Logan.

Catawba football coach Harvey Stratton watched Robbins play intramural football and talked him to coming out for the team. That changed the course of Robbins’ life.

Robbins was an all-conference receiver for the Indians. In 1964, he had three touchdown catches against Lenoir-Rhyne. He led the conference in 1965 with 36 catches for 675 yards and had touchdown catches of 77 and 84 yards.

“I wish I’d played better for Coach Moir in basketball at Catawba, but I ended up earning my scholarship on the football field,” Robbins said.

He did his student teaching at Salisbury’s Boyden High.

He was a good enough football player that he was in camp with the AFL’s Denver Broncos. He played in three exhibition games before suffering a knee injury.

It was football dreams that brought him to Richmond.

In 1968, he had a strong season for the Richmond Roadrunners of the Atlantic Coast Football League, with 46 receptions for 716 yards and six touchdowns. His quarterback was Al Woodall, who had quarterbacked Duke and would move on from the Roadrunners to back up Joe Namath with the New York Jets.

“It was a good league, a lot of guys who had been with AFL or NFL teams or guys who would make it,” Robbins said.

Guys such as Oakland Raiders running back Marv Hubbard and New York Giants tight end Bob Tucker.

By 1970, knee injuries had ended Robbins’ playing career, but, by then, he had found his calling as a basketball coach, first in junior high and then at Thomas Jefferson High in Richmond.

In 1974, he married Bunny Baker, a teacher from Mount Holly, a next-door neighbor to Gastonia. They met at a party in Virginia. Robbins said it was destiny.

He got married in a white suit, and it became his good-luck charm. He would wear a white suit in a lot of CIAA championship games.

Robbins’ 1975 Thomas Jefferson team won a 3A state championship.

In 1978, Virginia Union hired Robbins, a history-making hire that upset some people because it took a coaching opportunity away from a Black coach.

Robbins didn’t see it as a huge deal. Almost all of the high school kids he’d been coaching had been Black.

“To me, I was just going across town to coach better, stronger and older kids,” Robbins said.

Robbins was hired by Tom Harris, who had coached Virginia Union basketball from 1950-74 and who had been watching Robbins coach for years. Some Virginia Union fans wanted a bigger name and at least one former NBA star was interested in the job, but it came down to dollars. Robbins came at a bargain price.

“They asked me how much I was making as a high school coach, and I told them $12,000 a year,” Robbins said. “Virginia Union said they could match that. But my first college paycheck was for less than I’d been making in high school because now they were taking out for the insurance.”

He went to work — and won and won and won. Year after year.

It took time, but his fellow CIAA coaches accepted, respected and eventually befriended a man dubbed by the media as “The White Shadow,” a reference to a television show that aired from 1978-81. The central figure of that program was a white coach who guided a predominantly Black high school basketball team.

Robbins became good friends with North Carolina coach Dean Smith. That opened doors for him. Smith got him on the list for clinics and for national and international coaching opportunities.

“I used to love to go and watch Dean’s teams practice,” Robbins said. “The best coach ever. He got a lot more done in a practice than I ever did.”

Robbins’ teams won with a system.

The priority always was defense, a defense that confused opponents who had a hard time identifying what they were dealing with.

“When he was coaching Winston-Salem State, Coach (Big House) Gaines gave me the best compliment I’ve ever gotten,” Robbins said. “He said, ‘Dave, I’ve watched three films of you guys and I have no idea what you’re doing.’ ”

Robbins’ key offensive concept was to determine the effective shooting range of each of his players.

“If we’d determined that your effective shooting range was 12 feet and you went out and shot from 15 feet, then you got a seat next to me,” Robbins said.

He was interviewed by four Division I programs in Virginia, but was never hired. He wasn’t upset about it. He was happy in Richmond, happy to be part of the CIAA, content to be coaching an HBCU school.

He stepped away from the hardwood in the spring of 2008.

“Thirty years at Virginia Union was a good round number,” he said. “I could have gone another year or two, but I didn’t think I could make it 35.”

Robbins’ record at Virginia Union was a remarkable 713-104, a winning percentage of 78.6 percent. His teams won 14 CIAA championships.

The first Hall of Fame for Robbins came when he got the call from Catawba in 1998.

“That first one — that was like that first girlfriend,” Robbins said. “You remember it.”

He also would be enshrined by Virginia Union, the CIAA, Thomas Jefferson High, Gaston County, the Virginia Sports Hall of Fame, the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame. and the Small College Basketball Hall of Fame.

The late Moir and Robbins’ former Catawba teammate Tom Childress advocated for Robbins to be chosen for the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame for many years, and it finally happened for him.

When you look at Robbins’ coaching record, it’s a no-brainer, but some things are hard to explain. This wide-ranging Hall class includes everyone from NFL stars Torry Holt, Sam Mills and Timmy Newsome to 1970s basketball standout Henry Bibby to Luke Appling, who was a baseball star back in the 1930s and 1940s.

“I was out of sight and out of mind, I guess,” Robbins said. “It’s been 55 years since I lived in North Carolina. A lot of people don’t realize I’m from the state.”

Robbins will turn 80 this September, but he’s still sharp, still hilarious.

He was in town last Monday to see Catawba and old friends. Catawba men’s basketball coach Rob Perron and Livingstone coach James Stinson had him speak to their teams.

Robbins has an endless supply of stories, like the one from June 1994 when the Houston Rockets, led by Hakeem Olajuwon and Robert Horry, were taking on the New York Knicks, with Patrick Ewing, John Starks and Oakley, in the NBA finals.

Oakley sent Robbins two tickets for a game at Madison Square Garden. Robbins was directed to his seats, which were right on the floor, right on top of the action.

“Madonna is on one side of me and Maury Povich is on the other,” Robbins said with a grin.

Oakley spotted Robbins and walked over . Everyone did a double-take when he spoke to the ordinary-looking guy between the celebrities.

“How ya doing, Big Fella,” Oakley said.

“Doing well, Big Fella,” Robbins answered.

Induction ceremonies for the North Carolina Hall of Fame Class of 2022 will be in Raleigh on April 22.

More Sports

SportsPlus

How to Watch Big South College Basketball Games – Friday, November 8

There are four games on the college basketball schedule on Friday that feature Big South teams. That includes…

How to Watch North Carolina Central vs. Gardner-Webb on TV or Live Stream – November 8

The Gardner-Webb Runnin’ Bulldogs (0-1) battle the North Carolina Central Eagles (0-1) on Friday, November 8, 2024 at…

AAC Football Scores and Results – Week 11 2024

The Week 11 college football schedule includes six games with AAC teams involved. Keep reading to see up-to-date…

Sun Belt Football Scores and Results – Week 11 2024

College football Week 11 action includes five games featuring Sun Belt teams. Check out the article below to…

College Basketball Picks Against the Spread: A-10 Games Today, November 8

The A-10 college basketball slate on Friday, which includes the George Mason Patriots squaring off against the Marquette…