KANNAPOLIS — In 2019, Dontae Jimmie attended a “kid’s science camp” at the Yukon River fish camp in Alaska led by Dr. Mary Ann Lila, professor at N.C. State University, and Dr. Kriya Dunlap, associate professor at University of Alaska-Fairbanks. Jimmie, now a rising senior in high school, lives in the village of Northway, Alaska, population 338. This month, Jimmie, along with five other Alaska Native students, accompanied by Dr. Dunlap, traveled more than 4,000 miles to Kannapolis (population nearly 55,000) for another educational enrichment experience: one hosted by Dr. Lila at NC State University’s Plants for Human Health Institute (PHHI).

At the fish camp, students collected biological specimens (samples of wild Alaska native plants) from the area to run “Screens-to-Nature” biodiscovery assays. One goal was to recognize the value of their native resources and the potential for yet-to-be-recognized health applications. The experiments were designed to be carried out in the field without the need for high tech equipment. The kids ran around by the riverbank and carried out their science experiments over a two-day period on a folding table set up under a tent.

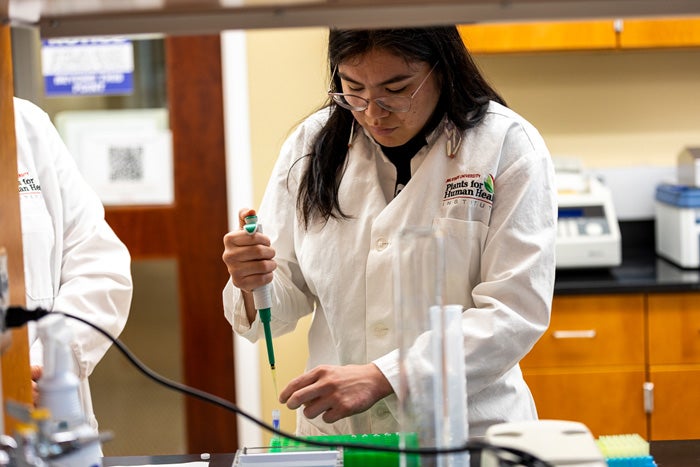

The opportunity to visit PHHI at the North Carolina Research Campus offers a chance to experience the high-tech side of science. The students put on their lab coats and paired up at the shiny black lab benches to practice micropipetting, run a simulated Covid PCR test, prepare a gel electrophoresis, and use a refractometer to evaluate fruit quality. They also repeated the biodiscovery kits under a controlled environment and discussed the challenges and limitations of field experiments. Of course, though, in the lab they didn’t have access to the diversity of biological samples that had been available in Alaska.

Laura Ekada, from Nulato, Alaska, is an undergraduate at the University of Alaska-Fairbanks, and took Organic Chemistry with Dr. Dunlap this past year. Her takeaway from the experience is exactly what Lila and Dunlap hoped to achieve. Ekada says, “I was introduced to a facility where I got to see science in action, making it feel more plausible for me. I can see myself here.”

Coupling Research and Outreach

It’s not uncommon for research grants to include an outreach component. In this case, the USDA grant, Back to the River: The science behind Alaska’s traditional subsistence lifestyle, aims to evaluate the phytochemical activity of the native Alaskan blueberry and other wild native plants from the tundra. Lila said, “Our goal in this grant was to emphasize to the students the outstanding health-related properties of their wild plants, which are already well established in Alaskan traditional ecological knowledge. We combined bioassays to reveal plant health-related properties with research on sled dogs, which are a pervasive feature in Alaskan life, and can serve as a sentinel for human health. That is, the racing sled dogs are a wonderful model to mimic human health responses to eating Alaska native plant resources especially combined with intense physical exercise.”

This student outreach provided the opportunity to demonstrate how Alaskan native resources can provide value for people outside of the Native population, if we can capture their bioactivity in food products or dog treats. In addition to the lab explorations, the group toured the NC Food Innovation lab and met with food scientists to learn how resources can be transformed into practical, food-grade ingredients. The students met with professors who have used wild berries in clinical trials and in product development, and they met with local industry partners who are interested in expanding on their research to create new products.

Lila and Dunlap have been working together for several years on this grant to evaluate the effect of native Alaskan blueberry consumption on inflammation in sled dogs. Dunlap’s father raced sled dogs professionally, so she has a wealth of knowledge and experience with their training regimen and their physiology. Her career path led her to biochemistry where her research, in part, includes looking at the effects of the phytochemicals in native Alaskan plants, like Vaccinium uliginosum or the “bog blueberry” on human (and animal) health.

Lila explains that while sled dogs may at first glance seem to be an unusual pre-clinical choice to evaluate health effects, their defined breed characteristics, controlled diet and controlled exercise allow for better dietary intervention observations. In this particular research project, the dogs were fed wild Alaskan blueberries in addition to their usual kibble. After a period of exercise, a blood sample was collected to test for biomarkers of inflammation. The hypothesis is that the phytochemicals in the blueberries will reduce inflammation and provide immune protection after exercise. Animals (and humans) are most vulnerable to viral infections after intensive exercise, and a simple intervention like dietary berries can boost immunity for an athlete.

As the research continues, Lila and Dunlap hope to involve more undergraduate and graduate students to work on specific aspects of the project. Their excitement about their research inspires students about career possibilities and underscores the value of their native berries and the value of their health benefits.