Charleston lived out his childhood dream of flying

Published 12:00 am Sunday, July 24, 2022

By Kenneth L. Hardin

For the Salisbury Post

SALISBURY — When Ray Charleston was 10 years old, he knew how to dream big while growing up in the Granite Quarry-Dunn’s Mountain area in the 1960s. Once he got his first taste of aviation, he knew it would be his life’s ambition.

On a trip to Ohio to visit his grandparents, he took his first airplane ride. As he boarded the Eastern Airlines jet, the door to the cockpit was open rendering him frozen and amazed at the view. Every summer thereafter for the next five years, he hopped on a plane with that same amazement each trip. Although he was a passenger, Charleston had much bigger flight plans in mind. He would be determined to see them come true, eventually sitting in the cockpit.

During his senior year at East Rowan High School in 1974, Charleston sat down with a guidance counselor asking what the best route would be to realize his dream. The military was recommended, but he was not ready to make that commitment. He opted to spend the next two years completing an electronic technology certification program, which he reasoned would help him on his journey to a pilot’s seat. At 20 years old, he took the educator’s advice and trekked down to the Air Force recruiting office. He told the recruiter that even if he couldn’t be a pilot, he wanted to be “part of a flight crew on a large aircraft.” Unfortunately, the dream was deferred as he was told there were no positions available.

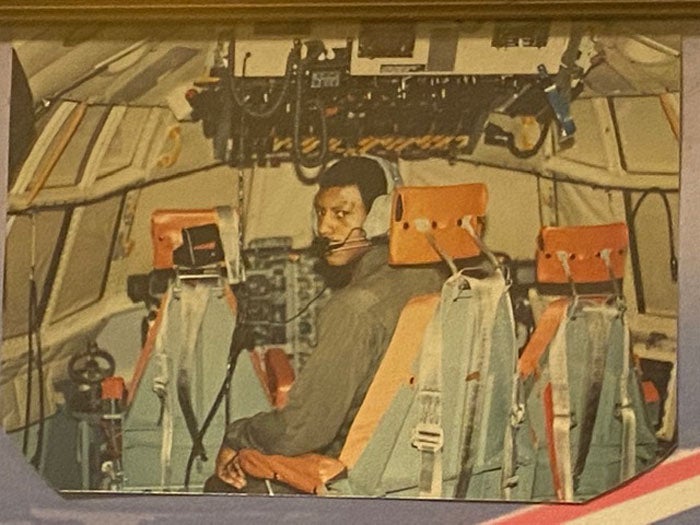

On his way out, he saw a poster for a Coast Guard Aviation position on a C-130 cargo plane. He walked excitedly into the recruiting office and secured a place in history as one of the first and only a few Blacks who would serve as a Coast Guard flight engineer at the time. Charleston admitted his path wasn’t easy and the route to realizing his dream had bumps in the road, but he was determined. On his journey he always remembered his father’s advice: “No one owes you anything. You have every opportunity to accomplish what you want if you work hard enough for it.”

He quickly realized the path to becoming a flight engineer would be challenging. The entry process for the elite training program was competitive with a five-year waiting list. As a new enlistee, he was at the bottom of the totem pole, but he remained undeterred. Charleston accepted other assignments while waiting for admission. He took an assignment serving on the White House Presidential Honor Guard under then-President Gerald Ford. He was told that to become a flight engineer he would have to become a mechanic, so he completed requirements to become an aviation machinist mate. While continuing to wait on admission, he took another assignment serving as the personal driver for the Coast Guard 5th District chief of staff. This was a blessing in that with the relationships he forged with senior officers, he was moved up on the waitlist and accepted into the aviation program two years early. He learned how competitive the three-month elite training program was as there were 15 others vying for the one slot he received. Out of the 25 total participants, he was the only Black applicant, but didn’t feel any level of intimidation. To ensure success, he sought out tutors and extra help with the demanding course load. It paid off as he scored 98% on his post completion ground test, officially making him an HC-130 flight engineer.

Charleston beamed while discussing his role supervising five enlisted crew members and some of the exotic places around the globe he was able to visit. He talked of landing at both the North and South Poles, crisscrossing the ocean rescuing missing boaters, conducting drug interdiction in South America and spending time in his favorite destination, Alaska.

He received an award from Lockheed Martin for amassing 8,000 flight hours, far exceeding the typical 5,000 in the air. He realized his flight dream, sharing he spent 500 hours at the helm of the massive cargo aircraft. A special moment in his career was when he invited his dad to Coast Guard Air Station Borinquen in Puerto Rico to see his work firsthand.

He got emotional recounting his father’s pride as he said, “I didn’t know you did all of this. I thought all you did was mess with planes.”

To sum up his life experience, Charleston said, “I never thought I would’ve been able to live my dream. I got to see and experience so much. A lot of people tried discouraging me, but I kept pushing. Young people, never give up on your dreams. If it looks like you can’t accomplish something, put it out of your mind and do it.”

Kenneth L. (Kenny) Hardin is an Air Force veteran and founder of the Veterans Social Center located in the West End Plaza.