Crowd gathers to reflect on 1906 lynchings, discuss modern-day parallels

Published 12:10 am Monday, August 7, 2017

By Josh Bergeron

josh.bergeron@salisburypost.com

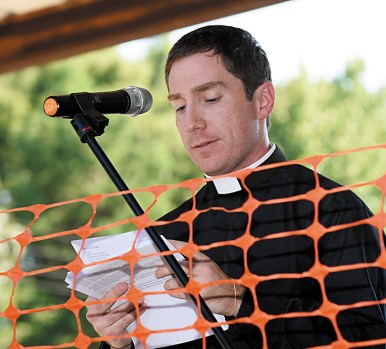

SALISBURY — The South hasn’t dealt with its tragic past and that’s why, at times, it seems doomed to repeat it, said the Rev. Stuart Taylor of Salem Presbytery.

On Sunday, Taylor spoke briefly to about 170 people gathered to discuss a triple lynching in 1906 and modern day similarities. Addressing the crowd, Taylor said the event wasn’t organized because Salisbury is a bad place. Instead, the event was intended to remember that lynchings occurred across North Carolina and the southern U.S, he said. Lynchings were common across the South, and the crowd of people were gathered to learn from the past, Taylor said.

Sunday’s event brought people of multiple ethnicities and religions. In attendance were history professors, pastors and community leaders. Multiple descendants of those lynched in 1906 attended Sunday’s event but did not want to be identified publicly.

The event started at the Salisbury Civic Center and ended near the location where an angry mob lynched three black men — John Gillespie, Jack Dillingham and Nease Gillespie.

The Gillespies and Dillingham were accused of murdering members of a white family who lived in the Unity Township at Barber Junction. Isaac Lyerly, his wife and two of their children were bludgeoned in a gruesome ax murder in July 1906.

Just after their trial started, the Gillespies and Dillingham were pulled from the jail by a mob reported to number 3,000 people. The mob walked the three black men to an area known as Henderson Woods. It’s at that location — near the intersection of Long and Gillespie streets in Salisbury — where the three black men were hanged. Their bodies were also mutilated and riddled with bullets.

Only one person — George Hall — was charged and convicted of a crime in connection with the incident. He received a sentence of 15 years of hard labor. In a book about the lynching, UNC history professor Claude Clegg wrote that the conviction was a first in North Carolina.

On Sunday, Clegg said the lynching should not be considered ancient history. He said 111 years is not that long ago.

“The more we can understand what happened during that time period the more we can understand our current time,” he said.

He said it’s possible to draw a direct line of descent from the time period in which lynchings occurred to the modern-day criminal justice system.

Seth Kotch, also a UNC history professor, gave several of those modern-day examples. One such example included black men receiving harsher sentences than white men accused of the same crime.

“The long arc bending towards justice is not always as comfortable as we might like,” he said.

Pastor Anthony Smith of Mission House joined Kotch and Clegg on a panel discussion during Sunday’s event. Responding to one question, Smith listed the “school-to-prison pipeline” as one local example of an injustice disproportionately affecting black men.

The school-to-prison pipeline is a phrase used to describe contact that students have with the criminal justice system because of policies implemented and decisions made by public schools.

It’s important to have difficult, deep conversations about those types of issues, Smith said.

Later, panel moderator Mike-o Martelli asked Kotch whether racial disparities in criminal sentencing should be considered “state-sanctioned, racially motivated terrorism.” Martelli preceded his question by saying lynching has been described as racially motivated terrorism.

Kotch responded affirmatively.

“The answer is yes, and we don’t want to parse the use of the word terrorism because we want to remember that the forms of terrorism that were used during the peak of the lynching crisis in the 1890s were homes burned to the ground with families in them and the brutality of lynchings,” Kotch said.

At one point during the panel, Clegg used the opioid epidemic as an example of how word choice can change based on the race affected.

“It’s been interesting for me to look at the language about it,” he said.

Clegg hesitated for a moment before being encouraged by the crowd to speak openly.

He said increasing rates of opioid overdoses across the nation are described as a health-based crisis rather than crime. The fact that increasing rates of overdoses affects mostly white Americans is the reason for the use of the words “crisis” or “epidemic,” he said.

“I don’t remember there being conversations about the crack epidemic,” he said to a round of applause.

Much of Sunday’s event focused more on the future and modern-day manifestations of racism than details of the 1906 lynching. The two-hour program at the Salisbury Civic Center involved prayers from members of different faiths, proclamations by local officials, a performance by Triple Threat Dance Company, music and a panel that involved Smith and the history professors.

Salisbury Mayor Karen Alexander issued a proclamation proclaiming Aug. 6, 2017, as a day that Salisburians should dedicate to truth, healing and reconciliation. East Spencer Mayor Barbara Mallet also issued a proclamation related to Sunday’s event.

After the program ended at the Civic Center, the crowd of people traveled to the intersection of Long and Gillespie streets. At that location, a large tree in a grassy field near railroad tracks is where the 1906 lynching reportedly occurred. There’s also speculation that the lynching may have occurred at another nearby tree.

Gathered near the location of the lynching, the crowd of people held a short worship service that involved scripture readings, hymns, a reading from Clegg’s book and a call-and-response in memory of Rowan County residents killed in lynchings.

In 1883 a man named Lawrence White was lynched.

In 1902, James and Harrison Gillespie were lynched. The exact nature of the relationship is not clear, but James and Harrison Gillespie were related to John and Nease Gillespie, Clegg said.

Sunday’s event also invoked the 1930 lynching of Laura Wood.

Asked about the importance of Sunday’s event, attendee Kenneth Miller said Salisbury and Rowan County are a family whether local residents like it or not.

“It would be like having a household that fights all the time, nothing gets done and nobody is happy,” Miller said. “But if you can heal that household, then you have a happy community and a happy house. That’s what we want.”

Contact reporter Josh Bergeron at 704-797-4246