Travel during Jim Crow era: ‘Green Book’ did not overlook North Carolina, Salisbury

Published 12:10 am Sunday, February 17, 2019

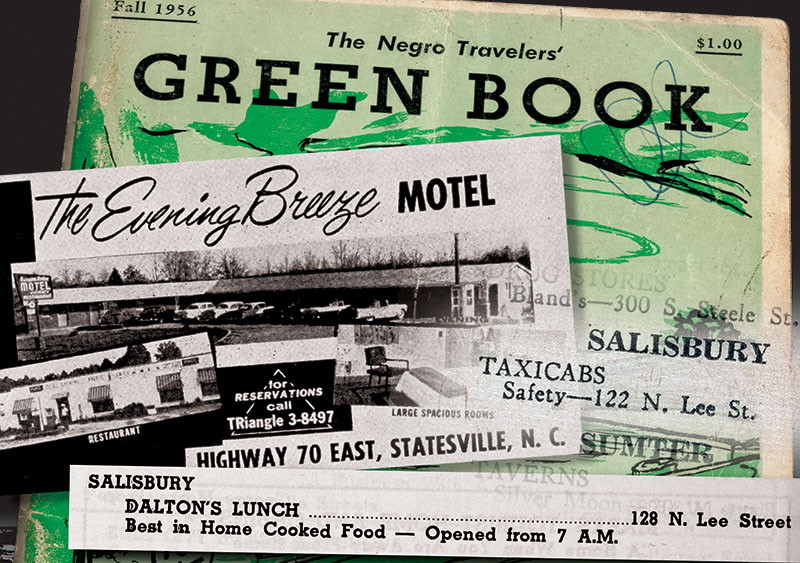

- Images courtesy of New York Public Library Digital Collections - The Green Book showed which businesses were friendly to traveling African Americans. Two businesses in Salisbury, Dalton's Lunch and Safety Taxi, were included in the book. Graphic by Andy Mooney

SALISBURY — As a child growing up in Salisbury, Raemi Evans often would travel with her family by car to visit relatives and friends in Connecticut and Massachusetts.

For those trips north, Evans has a strong memory of her parents making sure they had enough lunches packed for them to reach Pennsylvania at least and not have to stop anywhere to eat.

“Crossing the Mason-Dixon Line, you felt comfortable going to some of the restaurants, but not completely,” Evans, a black woman, says today looking back more than 50 years.

Traveling through the segregated South back then was a different, potentially more dangerous proposition.

Maybe her parents relied on it — it’s probably not something they would have shared, she says — but Evans didn’t know then of the “Negro Motorist Green-Book” or the “Negro Travelers’ Green Book.”

Published from 1936-66, this traveler’s guide contained names of hotels, restaurants, service stations, tourist homes, taxi services, roadhouses, barber shops, night clubs and more that were considered safe places for blacks to stop and patronize on their trips.

Lisa Withers, a research historian for the N.C. African American Heritage Commission’s Green Book Project, describes this traveler’s guide as “a tool for navigating unknown places.”

The book’s existence has, of course, been thrust into national consciousness most recently by “The Green Book” movie, starring Viggo Mortensen as Tony “Tony Lip” Vallelonga and Mahershala Ali as Dr. Don Shirley.

Interestingly, Salisbury’s Safety Taxi stands among just five North Carolina Green Book places identified so far that are still in business.

Today’s Safety Taxi owner, Archie Shaver, acknowledges he had never heard of the Green Book or even that Safety Taxi — thought to be at least a 90-year-old business in Salisbury — was a longtime entry in the guide.

Back then, Safety Taxi was located at 122 N. Lee St. It operates now at 226 E. Fisher St. and has alway been black-owned.

One other Salisbury location — Dalton’s Lunch at 128 N. Lee St. — was mentioned at least once in the Green Book. Not much is known about that establishment, though Hodge Evans, a brother-in-law to Raemi, remembers it.

Whether their parents relied on the Green Book or not during those days of Jim Crow and segregation, other Rowan County residents speak of similar travel precautions when they had to go to unfamiliar places.

Dee Dee Wright, who was heavily involved as a teenager in civil rights efforts in Greenville, South Carolina, said her NAACP Youth Council made a habit of staying in people’s homes when they traveled out of town.

Other options also were the homes above black-owned businesses. “That’s primarily how we used to negotiate those situations,” Wright said.

Wright said her family often traveled back and forth to New York with her uncle driving. She sat in the front passenger seat as the navigator, reading the maps and keeping her uncle awake.

“We knew we’d have to make it straight through,” Wright says. ‘There were no places we knew that we could stop.”

The exceptions might be service stations with “colored” bathrooms. But on long trips, they liked to pack sandwiches and, on more familiar routes of travel out of town, the adults knew the safer locations.

“That’s how you avoided a confrontation,” Wright said. “… That was a survival instinct. My mother knew where to go and where not to go.”

The Green Book simply aimed at making travel easier for blacks.

The foreword in the 1949 edition said, “With the introduction of this travel guide in 1936, it has been our idea to give the Negro traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trips more enjoyable.”

•••

Over the length of North Carolina’s Green Book Project, the commission will research each of the 327 identified N.C. sites in the Green Book editions, then develop an interactive web portal, allowing online visitors to explore each place and look through various “vignettes, stories and images.”

The Green Book Project also will lead to a traveling exhibit and a series of public programs “to highlight the experience of African-American travelers during the Jim Crow Era in North Carolina,” the Heritage Commission website says.

The state project is being funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

“The Green Book” movie’s story takes place in 1962 and is inspired by true accounts of what happened to Tony Lip, a white man and tough bar bouncer, who ends up being a driver for Shirley, a black classical pianist on a concert tour through the Deep South.

As they make their journey, they rely on the “Negro Motorist Green Book,” their travel guide as to what places will be safe for Shirley to patronize as a black man.

It’s a rocky relationship exasperated by the injustices they confront along the journey, but it also turns into a story of friendship and respect.

North Carolina’s Green Book Project was well underway before the movie, and Withers, the research historian, says there was “absolutely no connection” between the movie and the N.C. initiative.

Withers started her work with the Green Book Project in March 2018.

The movie’s popularity and its critical acclaim are happy coincidences.

“We’re glad that it helps getting the word out,” Withers says. “It makes it easier for us.”

In its research through January, the project had identified 66 physical structures mentioned in Green Book editions that are still standing in North Carolina (out of the 327 total N.C. entries over the 30 years).

Only four Green Book sites were believed to be in operation — Speight’s Auto Service and Friendly Barbershop in Durham, Magnolia House in Greensboro and Dove’s Auto Service in Kinston.

Withers was thrilled to learn this past week that Safety Taxi remains in business, even though at a different location.

“That is amazing,” Withers says. “I’m going to take note of that.”

Withers likes that the Green Book Project calls attention to the role local businesses had and the contributions they made during the days of segregation.

It showed that “even owning a business can have influence and implications,” she says.

Finding first-edition copies of the Green Book proves difficult. The N.C. Museum of History has a 1959 copy.

Withers says Duke University also has an original edition from the 1960s.

“We’re constantly asking if anyone has an original,” Withers says. “… Our current theory is people just threw them away when cleaning out their houses … especially after 1964 (when civil rights legislation was coming to the fore).”

A quick check with the Rowan Public Library and Rowan Museum Inc. did not turn up any Green Books in their collections.

The New York Public Library Digital Collections are a good source for viewing copies of the Green Book online.

•••

Withers says Victor H. Green, the travel guide’s publisher and for whom the Green Book is named, was a postal worker in Harlem, and his first 1936-37 edition listed only the places for African Americans in and around New York.

The Green Book’s reach broadened each year because of the “vast network” of connections Green had as a postal employee and submissions travelers would make to the Green Book, Withers says.

Green eventually retired and devoted more time to the travel guide, expanding into ad sales and strengthening circulation of the book. The 1961 edition had, for example, good-sized advertisements for Carson’s Service Station, Frank’s Grill and the Evening Breeze Motel, all in Statesville.

Located on U.S. 70 East, Evening Breeze Motel had a full-page advertisement.

Also in this general region around Salisbury, the Green Book’s 1961 edition mentioned two places in High Point — Club Fantasy at 603 E. Washington St. and the Kilby Hotel at 627 E. Washington St.

The Kilby was touted for “comfort, convenience and cleanliness.” Club Fantasy, the Green Book said, had good food and a pleasant atmosphere.

For Concord, the Green Book listed Town & Country Grill at 242 Lincoln St., offering “the best in home cooked food.”

In earlier Green Book editions, including issues in 1941 and 1947, a entry for Lexington was the D.T. Taylor Esso station.

Withers says Esso (which became today’s Exxon) service stations gained a reputation among African-American travelers as being friendly places and also where you might find a Green Book for sale.

Early on, people would write to the publisher for a copy or find it on news stands. After World War II, the travel industry began to grow, and Green increasingly targeted Green Book locations for ad sales.

He reached out to travel agents as well and the Green Book eventually spread to other countries.

•••

“Green Book,” the movie, has a scene taking place at a home in Raleigh, but Withers says the actual house shown in the movie is elsewhere, even though people have gone hunting for it in Raleigh.

Withers says she personally would like to know what creative licenses screenwriters took with Don Shirley and whether travel documents show exactly where Shirley stayed in Raleigh.

As you might expect, Green Book editions carried more entries for the larger N.C. cities of Charlotte, Winston-Salem, Raleigh, Greensboro, Durham and Wilmington than they did in smaller towns such as Salisbury, Statesville, Concord and Lexington.

Catrelia Hunter, who grew up in western Rowan County and attended the all-black R.A. Clement School, says she wasn’t aware of the Green Book as a youngster, but her family definitely knew the restaurants and hotels in the region where African Americans were welcome, or not.

When traveling, her family also packed their lunches. “We knew we had good food in the car, and that was it,” says Hunter, who has seen the movie and enjoyed it.

Her family also took caution in wherever they stopped for restroom breaks. “You had to be very careful,” Hunter says.

When Clement School took field trips to Washington, D.C., the students stayed in the African-American-friendly Dunbar Hotel, Hunter recalls. They did not chance eating out.

Principal George Knox brought the food back to the hotel for them.

Raemi Evans thinks of ice cream when she remembers Howard Johnson restaurants up north as being safe places for her family to stop. Howard Johnson’s touted 28 flavors of ice cream.

“I still chose vanilla,” Evans says, chuckling, “and to this very day, vanilla is my favorite.”

Contact Mark Wineka at 704-797-263, or mark.wineka@salisburypost.com. “The Green Book” is currently playing at the Cinemark Tinseltown USA theaters in Salisbury, with three different showtimes today, including 6:30 and 9:40 tonight.